clone Bulgarian Yogurt: From Ancient Traditions to Your Kitchen

Introduction to Bulgarian Yogurt

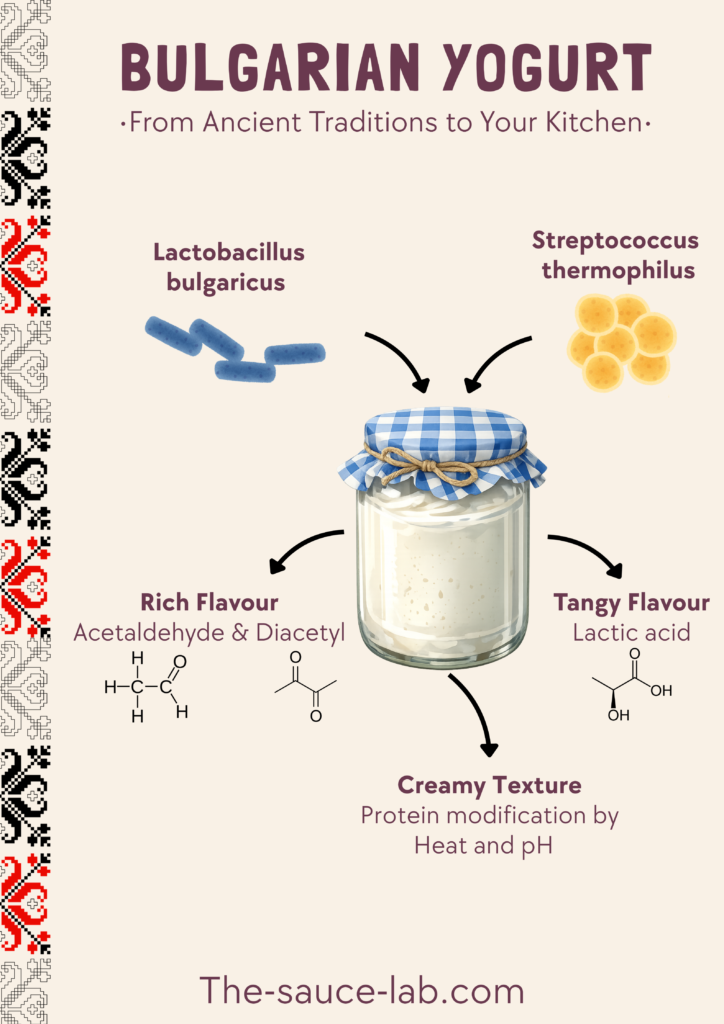

One of the best-known Bulgarian ferments is Bulgarian yogurt, also known as “kiselo mlyako” (sour milk). It is a thick, creamy, distinctly tangy fermented dairy product that has been enjoyed in Bulgaria and abroad for centuries. Bulgarian yogurt is not the only product containing Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus, the main bacteria found in yogurt. They are traditionally used alongside specific fermentation practices that enhance these two bacteria’s synergistic activity, producing a characteristic flavour and rich texture. These microorganisms have become closely associated with Bulgarian dairy culture and identity.

Bulgarian yogurt was and still is made in village kitchens, and the technique is passed from one generation to the next. Even though today you can buy a container of yogurt from the supermarket, making it at home is easier and tastier than you might think.

The Deep Roots of Bulgarian Yogurt

Early Origins of Fermented Dairy

Fermented dairy traditions in Bulgarian lands emerged gradually, shaped by successive populations—from Neolithic farmers, through Thracians, Slavs, and proto-Bulgarians—each contributing techniques and preferences that eventually converged into the yogurt (kiselo mlyako) known today (1,2).

Evidence for fermented milk has been found in Asia and Europe dating back to around 8000 B.C. This was most probably associated with the period when Homo sapiens domesticated milk-producing animals such as goats, sheep, and cows. Products resembling modern yogurts were found in Mesopotamia during the period 5000–6000 B.C. (1,2).

Bulgarian Geography, Tribes, and Early Yogurt Practices

Interestingly, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus can be found on some plants, and it is most likely that milk from milk-producing animals encountered plants containing the bacteria, thus accidentally souring the milk. An old tradition in Bulgaria is to put a particular plant species into already boiled milk and incubate it at 45 °C you will get yogurt with dense coagulum (3).

Bulgaria is located on the Balkan Peninsula between Western Europe and the Middle East and has an ideal climate suitable for the husbandry of cattle, sheep, and goats. This explains why Bulgarians have a rich tradition of milk fermentation. Findings from a Neolithic settlement in Azmashka (near present-day Stara Zagora, around 6000 B.C.), where remains of milk-producing animals were discovered, confirm that ancient tribes were keen on keeping domesticated animals (1,2).

The Thracian tribe Bizalti, who lived in regions of present-day Shumen, Targovishte, and Varna, were known to produce fermented dairy foods (1,2).

It is also known that proto-Bulgarians fermented mare’s milk in leather bags made from animals’ stomachs, a staple food for them during battles. This drink is called koumiss.

The Slavs prepared sura—a type of yogurt fermented in wooden barrels during the summer, which they consumed during the winter. Ancient Bulgarians most probably tasted the sheep’s yogurt made by both Thracians and Slavs and gradually replaced the mare’s milk they had used with yogurt.

Bulgarian yogurt gained recognition as early as 1542, when the French king François I was reportedly cured of diarrhea after consuming yogurt.

Scientific Recognition and Global Impact

As you have probably noticed, one of the bacteria responsible for yogurt fermentation is called L. bulgaricus. This is not a coincidence. In 1905, a Bulgarian medical student in Geneva, Dr. Stamen Grigorov, was the first to describe the bacteria responsible for yogurt fermentation. He identified a lactic acid–producing, rod-shaped bacterium—later named Bacillus bulgaricus (now Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus). This discovery inspired the future Nobel laureate and Russian biologist Élie Metchnikoff to speculate that the longevity of Bulgarian peasants in mountainous regions was due to yogurt consumption (1,2).

During the early 20th century, many physicians promoted yogurt consumption as therapy for certain digestive disorders. This medical enthusiasm coincided with the founding of Danone by Isaac Carasso, who was influenced by research on lactic acid–producing bacteria and their potential health benefits. Danone was founded in Barcelona and distributed yogurt through pharmacies, later expanding operations to France. Dairy products are a major part of the European diet, accounting for more than 45 billion metric tons consumed annually. EU countries produced 6.1 billion tons of yogurt through 2019. Beyond Europe, Bulgarian yogurt has had significant cultural and commercial impact in Japan, where it was introduced in the 20th century and became widely popular through its association with Lactobacillus bulgaricus and probiotic health benefits. There it is known as “Bulgaria Yoghurt” (ブルガリアヨーグルト) (4). During 2020, Bulgaria processed roughly 663 million liters of milk. Although Bulgaria produces a relatively small amount of yogurt, it is known for its high quality and cultural importance

What Bulgarian Yogurt Really Is

Flavour profile

At its core, Bulgarian yogurt is fermented milk. If you have authentic homemade Bulgarian yogurt, you will experience:

- Creamy texture

- Tangy flavour

- Mild sweetness

- Probiotic benefits

These flavour attributes come from the two main cultures that ferment the milk (L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus)—a relationship that has been studied and celebrated for its health benefits for generations.

Bulgarian yogurt is a traditional Bulgarian dairy food and perhaps the best-known food in the country.

Standards and How It’s Made

It is made with pasteurized milk inoculated with a starter culture of two LABs—Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus. Most Bulgarian yogurt is made from cow’s milk, but it can also be produced from goat, sheep, buffalo or a combination of different milks (cow and sheep or cow and buffalo) (5).

According to the Bulgarian Institute for Standardization, the final fermented yogurt should contain at least 10⁷ CFU/g of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and 10⁸ CFU/g of Streptococcus thermophilus (5).

Another important point is that the milk used to produce yogurt should not contain antibiotics or other inhibitory substances that could inhibit the growth of LABs (5).

The Bulgarian Institute for Standardization also has strict criteria for yogurt appearance. Its surface should be smooth and shiny, while the colour should range from white to creamy, with slight variations depending on the type of milk used. The coagulum should be smooth and homogeneous, with no visible whey separation. The flavour should be specific, pleasant, and characteristic of the milk used. In some cases, for example when sheep or buffalo milk is used, the consistency can be slightly granular (5).

Both industrial and homemade yogurt production follow the same principles.

Raw milk, which should be as fresh as possible, is filtered to remove solid particles and then pasteurized by heating to 93–95 °C for 15–30 minutes, followed by rapid cooling to 45–46 °C. The pasteurized milk is then inoculated with a starter culture consisting of L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus. This is generally done by three main methods: lyophilized starter, backslopping from an already made yogurt, or liquid highly concentrated starter used only in industrial production (5).

After inoculation, the milk is divided into clean vessels, capped, and incubated in a warm environment (for example, wrapped in a blanket, placed in an incubator at 44 °C ±2 °C, or using a sous vide setup). Depending on the starter, incubation lasts between 2 and 8 hours. After that, the yogurt is cooled first to 20 °C (room temperature) and then placed in a refrigerator at +2 °C to +6 °C, where it can be kept for a maximum of 20 days (5).

Тhe Ingredients You’ll Need to Make Homemade Yogurt

You don’t need much to make this yogurt at home — and the better your ingredients, the more rewarding the result:

- Raw milk – Whole milk works best for a rich and creamy yogurt

- Starter culture – Your favourite live Bulgarian yogurt (backslopping) or specific freeze-dried cultures containing L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus

- A thermometer – Temperature is everything

- Jars or containers – To incubate your yogurt

- Optional – Sous vide or incubation chamber

Choosing good-quality milk will elevate the result — after all, great yogurt starts with great ingredients.

Step by Step — Make This Bulgarian Yogurt at Home

Here’s how to turn simple milk into delicious Bulgarian yogurt:

- Strain the milk – Use a fine mesh strainer to prevent unwanted solids from passing through.

- Heat the milk – Warm it slowly to 93–95 °C for 15 to 30 minutes. This ensures that unwanted bacteria in the milk are killed and that milk proteins undergo proper changes, so they set better later.

- Cool to 45–46 °C – Rapid cooling is recommended to prevent contamination with other bacteria. This is also the ideal temperature for the cultures to thrive when they are added.

- Add your starter – Either add a spoonful (about 50 g) of live Bulgarian yogurt from a previous batch or use the amount of freeze-dried culture recommended by the producer (for 1–2 L, the amount should be at least 10⁸–10⁹ live cells per gram).

- Incubate – Keep your jars warm (around 44 °C ±2 °C) for 4–8 hours until the milk thickens into yogurt. A yogurt maker, warm oven, or insulated cooler can help.

- Chill – Cool the yogurt first to 20 °C, then place it in the refrigerator for at least a couple of hours to fully set and deepen the flavour.

Classic Bulgarian yogurt should be smooth, thick, and tangy. Let the culture do its work.

Using Bulgarian Yogurt

Bulgarian yogurt is delicious on its own, but it is also incredibly versatile.

Traditional Bulgarian Uses

- Breakfast or snack – Eat it alone or combined with nuts, granola, and fruit

- Tarator – Mix Bulgarian yogurt with cucumbers, garlic, dill, a pinch of salt, and a bit of oil for a classic cold Bulgarian soup. A great addition to tarator is crushed walnuts.

- Snezhanka (Snow White) salad – Strained Bulgarian yogurt, cucumber, garlic, salt, oil, and dill. Walnuts and parsley are also excellent additions.

- Cooking ingredient – Use it in marinades, baking, or creamy sauces

- Panagyurishte-style eggs – Poached eggs laid on top of Bulgarian yogurt flavored with garlic and topped with Bulgarian white cheese and piping-hot butter mixed with sweet paprika

- Soup thickener with yogurt and egg (zastroyka) – Yogurt-and-egg thickeners are very characteristic of Bulgarian cuisine. Almost every traditional soup uses some form of thickening, which gives the soup body and a finished texture. The thickener is made from egg yolk and Bulgarian yogurt and tempered with a small amount of hot broth to prevent curdling. Once the temperatures are equalized, the thickener is added to the soup under constant stirring.

Global or Alternative Uses

- Mast-o khiar – A Persian dish made with yogurt, Persian cucumbers, raisins, garlic, chopped walnuts, and spices such as mint, dill, parsley, and Damascus rose petals

- Yayla çorbası – A Turkish dish made with rice, yogurt, egg yolks, and herbs such as mint, purslane, and parsley. Variations occur throughout the Middle East.

- Tzatziki or cacık – A classic dip or sauce made from strained yogurt with cucumbers, garlic, salt, olive oil, vinegar or lemon juice, and herbs such as dill, mint, parsley, and thyme

How to Store It

Proper storage ensures you can enjoy your yogurt longer and safely:

• Keep it in a covered container in the refrigerator

• The yogurt is best consumed within 20 days.

• Freezing is not ideal — fresh is always best

Refrigeration slows fermentation by slowing down bacterial activity while preserving flavour.

Science Meets Tradition

At first glance, yogurt making seems simple — milk and two LAB cultures. Yet these bacteria transform milk into a product with creamy texture and unique taste.

1. Heating

Heating the milk has two main functions. First, it improves microbial safety by reducing pathogenic microorganisms. This heat treatment is neither UHT nor sterilization (autoclaving at 121 °C under pressure or 135–150 °C for seconds). Heating ensures that Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus have a better chance for rapid multiplication and acidification (6,7).

Second, heating modifies protein structure by denaturing whey proteins, helping form whey–casein complexes. Whey proteins consist of α-lactalbumin, β-lactoglobulin, serum albumin, and immunoglobulins. At temperatures above 70 °C, β-lactoglobulin unfolds and exposes thiol (–SH) groups (6,7).

Milk also contains nanostructures called casein micelles, suspended in the milk and composed primarily of αs1-, αs2-, β-, and κ-caseins in combination with inorganic phosphorus and calcium. κ-Casein, located on the micelle surface, forms a negatively charged layer that provides repulsion between micelles, ensuring non-aggregative behaviour at neutral pH.

During heating, micelles themselves do not denature, but κ-casein interacts with unfolded β-lactoglobulin, forming strong bonds and increasing micelle contact. This primes the micelles for aggregation. As L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus convert lactose into lactic acid, the pH drops, allowing modified micelles to aggregate and form a protein network that traps water, creating the characteristic yogurt texture (6,7).

2. Proto-cooperation

Streptococcus thermophilus and L. bulgaricus stimulate each other during fermentation in a symbiotic relationship. S. thermophilus produces pyruvic acid, formic acid, folic acid, ornithine, long-chain fatty acids, and CO₂, and reduces dissolved oxygen in milk, stimulating L. bulgaricus growth. It also produces lactic acid, lowering pH to optimal levels (6,7).

L. bulgaricus exhibits strong proteolytic activity, breaking peptides into free amino acids and producing putrescine, which stimulates S. thermophilus. This mutually beneficial relationship is called proto-cooperation and is essential for balanced growth, aromatic compound production, and pH reduction affecting yogurt texture (6,7).

3. pH Lowering and Flavours

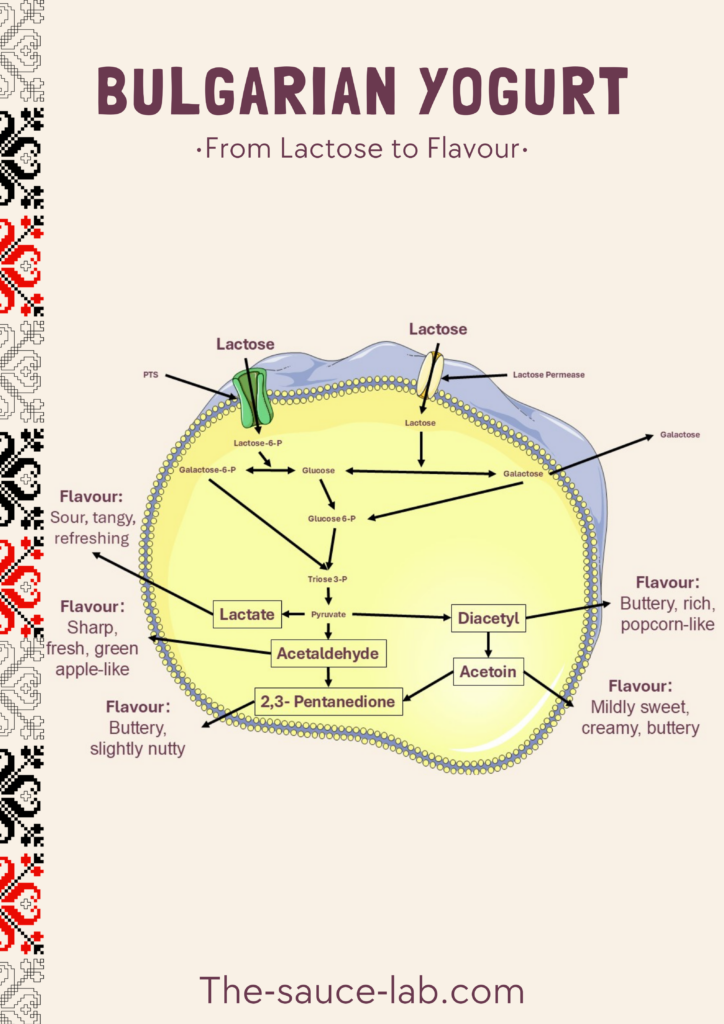

Lactose is a natural disaccharide composed of glucose and galactose and is the primary carbon source for yogurt bacteria. During fermentation, lactose metabolism produces lactic acid and volatile compounds that contribute to aroma and flavour (6,7,8).

The pH of milk strongly influences yogurt gel formation. It is lowered by the lactic acid production. At natural pH ( around pH 6.6), casein micelles are negatively charged and repel each other, which keeps the milk liquid. As L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus start to produce lactic acid, the pH drops to the isoelectric point of casein (around pH 4.6), which reduces the repulsion between the micells. This allows micelles to aggregate, forming the protein network that gives yogurt its gel-like texture (6,7,8).

Lactose enters bacterial cells via permeases or the phosphotransferase system (PTS) and is hydrolysed by β-galactosidase into glucose and galactose (or galactose-6-phosphate). Glucose enters glycolysis, while galactose-6-phosphate is metabolized via the tagatose-6-phosphate pathway. These processes produce compounds such as acetaldehyde, acetoin, diacetyl, and 2,3-pentanedione, contributing to Bulgarian yogurt’s distinctive flavour (6,7,8).

Interestingly, L. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus are not the only bacteria present in Bulgarian yogurt. Evidence suggests that additional species may also contribute to flavour development.

Product: Yogurt

Starter strains: L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, S. thermophilus

Additional microflora: L. helveticus, L. paracasei, L. fermentum, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides, Weissella confusa, Pediococcus acidilactici, Lactococcus lactis, Enterococcus faecium (6,7,9).

4. Amino Acids, Bioactive Peptides, and Health

During fermentation, LABs produce bioactive substances with positive health effects. Their proteolytic activity releases free amino acids and oligopeptides, including lysine, tryptophan, and L-arginine. Scientific evidence suggests that L-arginine and its precursors may have beneficial effects on cardiovascular health, endothelial function, hypertension, ischemia–reperfusion injury, and irritable bowel syndrome (7,10).

LABs also synthesize phosphopeptides that improve absorption of calcium, phosphorus, iron, and magnesium. Regular dairy consumption is associated with reduced risk of bone fractures (7,10).

Additionally, LABs can produce bacteriocins with antimicrobial properties. L. bulgaricus strain BB18 produces bulgaricin, active against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens, including Helicobacter pylori (7,10,11).

Yogurt consumption has been associated with improved lactose digestion, lower risk of type 2 diabetes, better weight maintenance, reduced risk of breast and colorectal cancer, and improved cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and bone health. While dairy consumption has been associated with prostate cancer risk, no clear difference has been observed between fermented and unfermented dairy products (7,10).

Final Thoughts

Making Bulgarian yogurt at home is easy and rewarding. The result is creamy, tangy yogurt that tastes better than most store-bought versions — while allowing you to experience microbiology firsthand and connect with a centuries-old culinary tradition.

So, heat the milk and let those microscopic creatures do their thing. Once you have tasted your first spoonful of homemade Bulgarian yogurt, you will understand why this humble food has captured hearts and kitchens around the world.

References:

1. Fisberg, M., & Machado, R. (2015). History of yogurt and current patterns of consumption. Nutrition Reviews, 73(Suppl 1), 4–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv020

2. Teneva-Angelova, T., Balabanova, T., Boyanova, P., & Beshkova, D. (2018). Traditional Balkan fermented milk products. Engineering in Life Sciences, 18(11), 807–815. https://doi.org/10.1002/elsc.201800050

3. Michaylova, M., Minkova, S., Kimura, K., Sasaki, T., & Isawa, K. (2007). Isolation and characterization of Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus from plants in Bulgaria. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 269(1), 160–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00679.x

4. Meiji Bulgaria Yogurt Club. (n.d.). About Meiji Bulgaria Yogurt. Retrieved January 18, 2026, from https://www.meijibulgariayogurt.com/en/

5. Bulgarian Institute for Standardization (BDS). (2010). BDS 12:2010 — Bulgarian yogurt (Kiselo mlyako). Sofia, Bulgaria.

6. Mahomud, M., et al. (2017). Reviews in Agricultural Science, 5, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.7831/ras5.1

7. Petrova, P., Ivanov, I., Tsigoriyna, L., Valcheva, N., Vasileva, E., Parvanova-Mancheva, T., Arsov, A., & Petrov, K. (Year). Traditional Bulgarian dairy products: Ethnic foods with health benefits. https://doi.org/

8. Özcan, T., Horne, D. S., & Lucey, J. A. (2015). Yogurt made from milk heated at different pH values. Journal of Dairy Science, 98(10), 6749–6758. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2015‑9643

9. Nemska, V., Logar, P., Rasheva, T., Sholeva, Z., Georgieva, N., & Danova, S. (2019). Functional characteristics of lactobacilli from traditional Bulgarian fermented milk products. Turkish Journal of Biology, 43(2), 148–153. https://doi.org/10.3906/biy‑1808‑34

10. Savaiano, D. A., & Hutkins, R. W. (2021). Yogurt, cultured fermented milk, and health: A systematic review. Nutrition Reviews, 79(5), 599–614. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa013

11. Simova, E. D., Beshkova, D. M., Angelov, M. P., & Dimitrov, Z. P. (2008). Bacteriocin production by strain Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus BB18 during continuous prefermentation of yogurt starter culture and subsequent batch coagulation of milk. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, 35(6), 559–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10295‑008‑0317‑x

Bulgarian Yogurt

Ingredients

Method

- Gather your ingredients.

- Strain the milk with the help pf a fine mesh strainer to prevent unwanted solids from passing through.

- Heat the milk by warming it slowly to 93–95 °C for 15 to 30 minutes.

- Cool down to 45-46°C by using your sink filled with cold water.

- Ad your culture. Either add a spoonful (about 50 g) of live Bulgarian yogurt from a previous batch (this amount is for about 500 mL of raw milk) or use the amount of freeze-dried culture recommended by the producer (for 1–2 L, the amount should be at least10⁸–10⁹ live cells per gram)

- Incubate by Keeping your jars warm (around 44 °C ±2 °C) for 4–8 hours until the milk thickens into yogurt. A yogurt maker, warm oven, or insulated cooler can help.