Rice: Core Cooking Physics (Foundational)

What happens when rice cooks

Rice cooking often involves practices shared through tradition. Those recipes usually share some form of inherited rules about the ratio of rice to water, washing and agitation of the rice, soaking time, and cooking time. While some of those recipes, traditionally shared in the family, may work, they rarely explain why different methods produce such different textures. When you think about it, there is a striking difference between the texture and flavour of rice used for sushi compared to one used for biryani. Fundamentally, most dishes that contain rice are governed by the same set of physical and chemical processes—starch gelatinization, water absorption, and heat-driven transformations—though different dishes deliberately stop the process at different points.

Understanding these principles will give control over texture and consistency rather than relying on guessing, trials, and errors. We will also recognize that rice varieties have differences in starch composition, which can modify the result.

Rice variety decides the direction.

Cooking method decides the outcome.

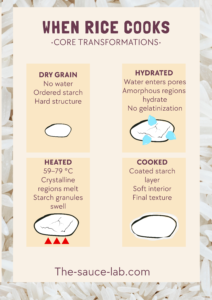

How Water, Heat, and Structure Transform Hard Rice into Food

In Post 1—Rice: Varieties, Structure, and Classification—we introduced rice as a biological material: the anatomy of the rice plant, the structure of the rice grain, rice varieties, and classification. Here, we will try to explain what happens when we cook rice—the physics and chemistry that happen inside the grain: how rice is hydrated, transfer of heat, starch granule swelling and melting, starch leaching into the water, and all the forces that can turn raw rice into a final dish.

It turns out that cooking rice is not simply combining water and raw rice; it is a complicated succession of physical events and transformations that are controlled by water, heat, and grain structure (1, 2, 3).

In this post, we will talk about the science of rice cooking in five distinct pillars:

- Is washing rice necessary

- Hydration: How Water Enters Rice

- Heat Transfer: How Heat Energy Moves into the Grain

- Starch Transformations: Gelatinization, Leaching, and Retrogradation

- Cooking Modifiers: Mechanical Forces, Fats, and Atmosphere

Let’s walk through them.

1. Is washing rice necessary?

Washing rice removes debris from the surface of the rice grain but also removes some of the proteins and lipids present in the bran.

Rice varieties with medium amylose content, mainly used in countries such as the Philippines, Japan, China, and Thailand, are generally washed 2–3 times before cooking it with a fixed water-to-rice ratio.

In India, Pakistan, and Iran, where the most commonly used rice varieties are high in amylose, washing is done 3–5 times before cooking (5).

Rice that is washed at least three times, compared to only once, shows better odour and taste.

Washing rice before cooking will NOT change the final texture of the rice—its firmness or stickiness. It also will NOT affect the structure of the starch or starch leaching during cooking. It should be noted that rice grains will start absorbing water when washed (5).

2. Hydration: How Water Enters the Grain

Hydration vs. Gelatinization — It’s not the same thing

Soaking rice makes it absorb water. When we take a close look at the architecture of the rice grain, we can appreciate the recurring layers—semi-crystalline regions and amorphous layers. Water first enters and hydrates the amorphous regions through cracks, endosperm pores, or damaged starch sites in the rice grain. This is not gelatinization; it is hydration. Gelatinization occurs in the range of 59–79 °C (138–174 °F), a temperature-dependent process that depends on the rice variety (2,5).

Interestingly, water intake is very rapid at first (0–30 min) and plateaus after ~120 min. In general, after the first 20 minutes, additional soaking (up to 120 minutes) does not significantly increase final moisture.

What does change with time is the internal microstructure:

- 0–60 minutes of soaking:

During soaking, the starch compartments inside the grain (amyloplasts) start to break down. Additionally, small pores form in the grain. As a result, the rice grain becomes softer, loses strength, and holds its shape less. - 60–120 minutes of soaking:

The end result of prolonged soaking is rice that is stickier and shows an increase in breaking energy (it takes more force to fracture the grain).

Softening occurs only in the outermost layers, and starch granules inside the rice do not swell, thus remaining raw (2). This process can be simplified by saying that hydration prepares the rice grain, but heat eventually transforms it.

Soaking = hydration

Cooking = heat + hydration → gelatinization

Hydration improves cooking by reducing hard cores, preventing cracking, and improving rice grain expansion. It also allows the rice grain to expand more, prevents cracking, and promotes more uniform cooking. Adequate hydration improves internal water distribution, contributing to more uniform cooking (1, 2).

If rice is cooked without sufficient hydration beforehand, water cannot reach the center for proper gelatinization, leaving a hard, chalky center even though the outer layers appear fully cooked. Conversely, if rice grains are soaked for prolonged periods (>120 min), texture quality declines (5).

How soaking time affects the grain

Tomita et al. (4) found that rice soaked at 10 °C ends up with higher moisture content than unsoaked rice once cooked. However, after the first 20 minutes, additional soaking (up to 120 minutes) does not significantly increase final moisture, meaning the grain saturates quickly (5).

What does change with time is the internal microstructure:

0–60 minutes of soaking:

The amyloplasts (starch granule compartments) begin to disappear, pores enlarge, and the cooked grain becomes less firm and less elastic. This makes the rice softer but reduces its structural strength.

60–120 minutes of soaking:

Surprisingly, the trend reverses. Rice becomes stickier, and its breaking energy increases, meaning it takes more force to fracture the grain. This shift is linked to deeper hydration reaching the core.

Interestingly, soaking rice in warm water helps it absorb moisture faster. Warm water activates starch-degrading enzymes, increasing sugars and amino acids and improving taste. Enzyme activation also assists in breaking parts of the cell wall, facilitating starch release and stickiness. Warm water refers to a temperature range of 25–40 °C (5).

Water Availability Controls Expansion

Water presence is important when cooking rice, and the amount of water is crucial. Here are three examples of water availability: 0.8, 1.6–2, and steaming (where water is unlimited).

When water is limited (0.8:1 water-to-rice), rice grains absorb water quickly, and water in the pot disappears early. At the proper temperature, gelatinization occurs but stops as soon as water is gone, resulting in limited grain expansion (5).

When water is moderate to high (1.6–2:1 water-to-rice), water is sufficient for hydration and grain swelling. Even after gelatinization begins, rice grains continue absorbing water, allowing expansion to continue longer. The result is a large, elongated, fluffy grain.

With unlimited water (steaming), water is continuously supplied to the grain surface. Hydration never runs out, allowing continuous expansion under heat. This produces the greatest expansion (>200%).

Rule of thumb: when water runs out, gelatinization stops immediately. Rice grain expansion continues only while water remains available (5).

3. Heat Transfer: How Energy Moves into the Grain

Traditional rice preparation methods such as absorption cooking, steaming, and agitation cooking heat rice grains from the outside inward. Each cooking style has its own heat transfer mechanism, generally via boiling water, steam condensation, or internal conduction (5).

A fast but disruptive method of cooking rice is microwaving. Microwaves excite polar molecules (water) within the grain, heating rice from the inside outward. Each method produces radically different outcomes, which will be discussed in more detail in a future post (5).

Heating: How Temperature Transforms the Rice Grain

The heating principles described below explain what happens to the rice grain under a controlled limited-water environment (LWM). LWM is used because it clearly illustrates the underlying physics. These transformations—gelatinization, diffusion, and structural breakdown—occur in all cooking methods, under different water and temperature conditions (5).

Once rice has absorbed enough water during soaking, heat takes over. Heating causes the main transformation—gelatinization—which turns raw rice into an edible form. Heating occurs in three stages:

- Temperature rise

- Boiling

- Braising (steam finish)

Each stage affects texture differently (5).

1) Temperature Rise Stage: How fast you heat matters

As temperature rises toward boiling, rice continues absorbing water. Heating rate affects how evenly the grain hydrates and gelatinizes.

Slow heating:

Rice spends more time in water before reaching boiling. This can cause early water depletion due to absorption and reorganization of the starch network, leaving the grain center incompletely gelatinized.

Rapid heating:

Rice reaches boiling quickly but lacks sufficient time to absorb enough water, resulting in uneven gelatinization between outer layers and the core (5).

During slow heating, mild enzymatic reactions increase total and reducing sugars, influencing sweetness and aroma. Holding rice briefly at 40–60 °C also increases amino acids and sugars through enzymatic activity.

Both overly slow and overly fast heating can lead to uneven gelatinization. Steady, controlled heating yields the best results (5).

2) Boiling and 3) Braising Stages: The big water uptake

During boiling, remaining unabsorbed water is rapidly absorbed by rice grains. Even during boiling, the grain center remains firm, indicating incomplete gelatinization. Boiling alone is not enough (5).

The final step is braising, where heat is reduced (while still simmering). Rice continues cooking, excess water evaporates, and water redistributes evenly within the grain (5).

4. Starch Transformations: The Chemistry of Texture

This is the heart of rice cooking.

Step 1 — Gelatinization

Gelatinization is the main chemical event in rice cooking. It transforms the interior of rice from hard to soft. To understand this process, we briefly revisit concepts from Post 1.

Each starch granule contains two main molecules:

- Amylose — long, mostly linear polymer located mainly in amorphous regions

- Amylopectin — highly branched polymer located in both crystalline and amorphous regions

Rice starch granules are small (3–8 µm) and packed into amyloplasts.

Gelatinization occurs when water enters the grain and crystalline regions lose their ordered structure. New hydrogen bonds form between water and amylopectin, causing swelling and loss of internal order. This process is influenced by proteins, lipids, grain structure, cooking method, and heating rate. Gelatinization is irreversible—you cannot uncook rice (5).

Step 2 — Starch Leaching (Surface Stickiness)

As rice is soaked, heated, boiled, and braised, starch granules absorb water, swell, and rupture. This leads to leaching—the release of starch and other solids into surrounding water.

As pressure builds, cell membranes and walls break, allowing starch and other compounds to escape. This process is accelerated by endogenous enzymes active between 20–80 °C (5).

Early stage (30–60 °C):

- Most leached material is non-starch and proteins (40–55%)

- Starch leakage is low

Middle–high temperature (70–100 °C):

- Starch and protein leaching increases significantly

- More amylose and amylopectin escape

Late stage:

Leaching decreases due to starch re-uptake and formation of a coated surface layer (5).

The coated layer: the rice grain’s natural “glaze”

During cooking, a thin layer of starch, broken cell wall material, and other solids forms on the grain surface. This layer (1–7 µm; 1 µm = 0.001 mm) contributes to firmness, gloss, and stickiness.

Stickiness depends on both the amount and type of leached starch. More amylose leakage results in less sticky rice, while more amylopectin leakage increases stickiness. Long-grain rice remains separate, whereas sushi rice becomes sticky due to higher amylopectin leaching (5).

Step 3 — Retrogradation (Cooling & Storage)

Once rice cools, reorganization of starch molecules begins. This process is called retrogradation (3,5). Retrogradation is hydration-dependent and suppressed by high water content. Rice stored with more water retrogrades more slowly.

Simply put, retrogradation explains why freshly cooked rice is soft, while leftover rice becomes hard.

5. Cooking Modifiers: Mechanical Force, Fat, and Cooking Atmosphere

Mechanical Agitation

Risotto and pilaf illustrate this principle. Stirring disrupts gelatinized granules, increases starch leaching (high amylopectin), and creates a starch emulsion that coats each grain while the core remains firm.

Fat Interactions

Coating rice with oil, as in pilaf, biryani bases, and paella, creates a physical barrier between grain and water. This slows water penetration, delays gelatinization, reduces starch leaching, and preserves aroma, resulting in discrete grains.

Cooking atmosphere: Steam vs. Liquid Contact

Steam-based cooking allows controlled hydration and gelatinization, preserving grain integrity and preventing excessive starch leaching. The result is glossy, separate grains.

Direct liquid contact increases starch loss, surface stickiness, and the risk of overcooking and structural breakdown.

Putting It All Together: The Physics of Perfect Rice

The key to cooking perfect rice is water, heat, and structure. Hydration determines when gelatinization begins, heat determines how it occurs, and structure determines final texture. When water runs out, gelatinization stops; when starch leaches excessively, structure collapses.

Different cooking techniques alter the same process but halt it at different stages. Once these factors are understood, rice texture is no longer arbitrary.

References:

- Hu, X., et al. (2025). Effect of the ratio of water to rice on the molecular dynamics of cooked rice starch during retrogradation: Implications for amorphous structure in gelatinized state. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 306, 141668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.141668

- Wang, L., et al. (2024). Effects of soaking conditions on water absorption, structure, gelatinization, and edible quality of rice and fresh wet rice noodles. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 278, 134621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134621

- Hirata, Y., et al. (2025). Effect of the ratio of water to rice on the molecular dynamics of cooked rice starch during retrogradation. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 306, 141668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.141668

- Tomita, K., et al. (2015). Effects of soaking temperature and time on the physicochemical properties of rice. Journal of Cereal Science, 65, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2015.06.004

- Tian, J., Ogawa, Y., Singh, J., & Kaur, L. (Eds.). (2023). Science of Rice Chemistry and Nutrition. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-3224-5

- The cover of this post used images from Freepik (www.freepik.com)