Sauce Béchamel: From the French Court to Global Comfort Food

Introduction

Béchamel is a classic white sauce, made from three simple ingredients: milk, butter, and flour. Despite its simplicity, it is one of the most used sauces in Western cuisine and serves as the foundation for many dishes around the world.

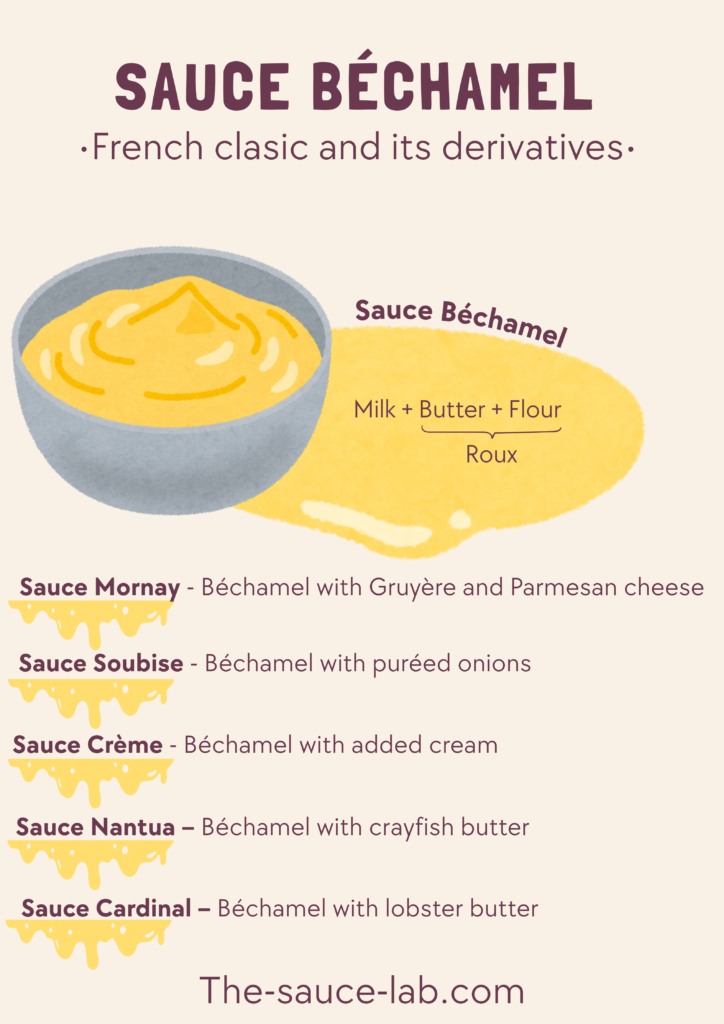

Sauce Béchamel is one of the five “mother sauces” coined by Auguste Escoffier in the early 20th century (1). Since sauce Béchamel is neutral, its creamy base can serve as a starting point for other classical French sauces such as sauce Crème, sauce Mornay, sauce Soubise, sauce Nantua , and sauce Cardinal.

Among the well-known non-French adaptations are Mustard Béchamel, Herb Béchamel, Sauce Bretonne, Sauce Cheddar, and Sauce Aurora

Sauce béchamel appears in many culinary traditions beyond France:

– In Italy as besciamella for baked pasta and lasagne.

– In Greece as besamél for moussaka and pastitsio.

– In Spain for different croquettes (croquetas).

– It is also present in the UK, Northern Europe, and Middle Eastern countries (Iran, Israel, and Egypt).

History of Sauce Béchamel

Legends suggest that Caterina de’ Medici was the person who introduced sauce Béchamel and many Italian culinary techniques to France.

Evidence suggests that this is just a myth. There is a lack of historical written records that associate Caterina de’ Medici with a white sauce or Béchamel. This association between Caterina and sauce béchamel appears only long after her death, most probably due to the romanticizing her role in culinary history. Most likely, the confusion comes from a book printed in 1719 (around 130 years after the death of Caterina de’ Medici), written by the police commissioner Nicolas Delamare (2). There, he states that many Italians followed Catherine de’ Medici and introduced various Italian table manners, dishes, and liqueurs to the French court.

In reality, the first written record of the use of a sauce containing roux and milk appears in the culinary text Le Cuisinier François, published in France in 1651 (3).

Culinary Usage of Béchamel Sauce

Sauce Béchamel is a simple yet versatile sauce and base in cooking. It is used in gratins, pasta dishes, and soufflés. It serves as a filling for croquettes, pies, and stuffed vegetables, and acts as the foundation for derivative sauces.

1. Gratin Dishes

• Potato gratin – thinly sliced potatoes topped with béchamel, often cheese, and baked in an oven.

• Vegetable gratins – vegetables such as cauliflower, broccoli, spinach, zucchini, or a mix.

• Seafood gratins – fish or shellfish baked with béchamel and a cheese topping.

• Doria (yōshoku – Western-style Japanese food) – sauce béchamel layered over rice, seafood, or chicken, topped with cheese and baked in the oven.

2. Pasta and Casseroles

• Lasagne – baked dish with pasta sheets alternating with fillings such as ragù bolognese, cheese, and sauce béchamel.

• Pasta al gratin – using different forms of pasta such as penne, fusilli, or cannelloni combined with béchamel and baked until bubbly.

3. Soufflés

• Cheese soufflé – béchamel forms the base mixed with egg yolks and whipped egg whites. Very commonly, the derivative sauce Mornay is used as a base.

• Vegetable soufflé – suitable vegetables include mushrooms, zucchini, cauliflower, broccoli, spinach, or asparagus.

4. Croquettes and Fritters

• Potato or fish croquettes – béchamel together with mashed potatoes, fish, or vegetables, shaped, breaded, and fried.

• Cheese croquettes – béchamel used as the creamy interior.

5. Derivative Sauces (Mother Sauce Use)

Béchamel is one of the five French “mother sauces,” forming the base for derivative sauces (4,5).

Classical French derivative sauces:

• Sauce Mornay – béchamel with grated Gruyère and Parmesan cheese.

• Sauce Soubise – béchamel with puréed onions.

• Sauce Crème – béchamel with added cream.

• Sauce Nantua – béchamel with crayfish butter or cream.

• Sauce Cardinal – béchamel with lobster butter.

Non-classical French derivative sauces:

• Mustard Béchamel – béchamel with added Dijon or whole-grain mustard.

• Herb Béchamel – béchamel with added fresh herbs like thyme, tarragon, or parsley.

• Sauce Bretonne – béchamel with mushrooms, carrots, leeks, and fish stock.

• Sauce Cheddar – béchamel with added cheddar cheese.

• Sauce Aurora – béchamel with tomato purée (most books categorise sauce Aurora as derived from another mother sauce—sauce velouté—but it also works well with sauce béchamel).

Alternative Ingredients for sauce Béchamel

Modernist Cuisine, Experimentation, and Variations

Although béchamel is truly French classical, it can be tweaked and adapts easily to modernist kitchens and dietary needs.

1. Fat Options

• Classic recipe: Butter

Alternatives:

• Brown butter (beurre noisette) – nutty, deeper flavour.

• Clarified butter / ghee – gives clearer flavour.

• Olive oil.

• Neutral oils.

• Infused fats with alliums, herbs, kombu, truffle.

• Vegan options such as cocoa butter or coconut fat, but only in small quantities in combination with olive oil.

2. Flour Options

Classic recipe: Wheat flour

Alternatives:

– Rice flour (gluten-free).

– Cornstarch (lighter texture, different mouthfeel).

– Gluten-free flour blends.

3. Milk Options

Classic recipe: Whole milk

Alternatives:

– Skimmed milk – creating a lighter sauce.

– Plant-based milks – oat, soy, coconut, cashew, or almond, preferably with added emulsifiers.

– Infused milk with bay leaf, onion, clove, and nutmeg, or more modern options such as kombu, smoked hay, or Parmesan rind.

4. Seasoning & Aromatics

Classic recipe: salt, white pepper, nutmeg

Variations:

– Infusion of the milk with bay leaf, thyme, onion, cloves, garlic, mushroom infusion, or modernist ideas such as kombu, lime leaf, smoked hay, or Parmesan rind.

– Spices such as different kinds of peppercorns (black, pink, long, Sansho, Sichuan, grains of paradise), or something that adds heat—cayenne pepper, etc.

5. Modernist Béchamel

Béchamel sauce without roux. Simply heat the milk and use hydrocolloids and emulsifiers to thicken the milk to create a modernist béchamel (4).

Preparation of Classical Béchamel Sauce

The secret to a good béchamel lie in the proper preparation of the roux, temperature control, and gradual incorporation of milk. When done correctly, the sauce is smooth, glossy, and lacks a floury taste.

(A roux is a mixture of equal parts fat and flour, cooked together to form a paste.)

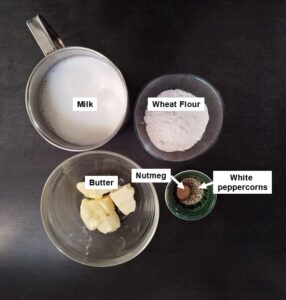

Ingredients for Classic Béchamel Sauce

Butter: The use of unsalted butter is preferable for seasoning control.

Flour: All-purpose wheat flour is ideal. It should be cooked slowly and thoroughly to remove raw flour taste.

Milk: Warm whole milk is more easily incorporated, thus preventing lumping.

Nutmeg: Freshly grated nutmeg is traditionally used—it adds warmth without overpowering.

Salt & White Pepper: White pepper keeps the sauce visually clean and adds gentle heat. Salt to taste.

Step-by-Step

- Prepare the milk:

In a saucepan over low-to-medium heat, gently warm the milk. At this stage, you can infuse the milk with aromatics (see above). - Make the roux:

Meanwhile, melt the butter in a saucepan over low-to-medium heat. After the butter melts, add all the flour and stir continuously for 1 to 3 minutes. Be sure not to brown the roux. After around 3 minutes, remove the pan from the heat and let it cool slightly. - Incorporate the milk:

Gradually add the warm milk while whisking constantly to prevent lumps. After adding 3–4 ladles of milk and incorporating them into the sauce, you can add the remaining milk at once.

Note: Some chefs pour cold milk all at once over the roux. This method saves time and one cooking dish from cleaning, but there is a higher chance of forming lumps.

- Cook the sauce:

Bring the sauce to a gentle simmer, stirring until thickened and smooth—up to 10 minutes. (Some authors recommend simmering the sauce for 30–60 minutes and skimming the skin regularly to remove milk proteins and trapped starch and fat.) - Season:

Season with salt, white pepper, and freshly grated nutmeg. - Use immediately or cover:

Cover with parchment or plastic wrap touching the surface to prevent skin formation.

Classical Ratios for Béchamel Sauce

Depending on the consistency of the sauce, the following ratios can be used (for 500ml milk:

| Consistency | Roux | Fat | Flour |

| Thin | 90 g (3.17 oz) | 45 g (1.59 oz) | 45 g (1.59 oz) |

| Medium | 120 g (4.23 oz) | 60 g (2.11 oz) | 60 g (2.11 oz) |

| Thick | 180 g (6.34 oz) | 90 g (3.17 oz) | 90 g (3.17 oz) |

The Science of Béchamel Sauce

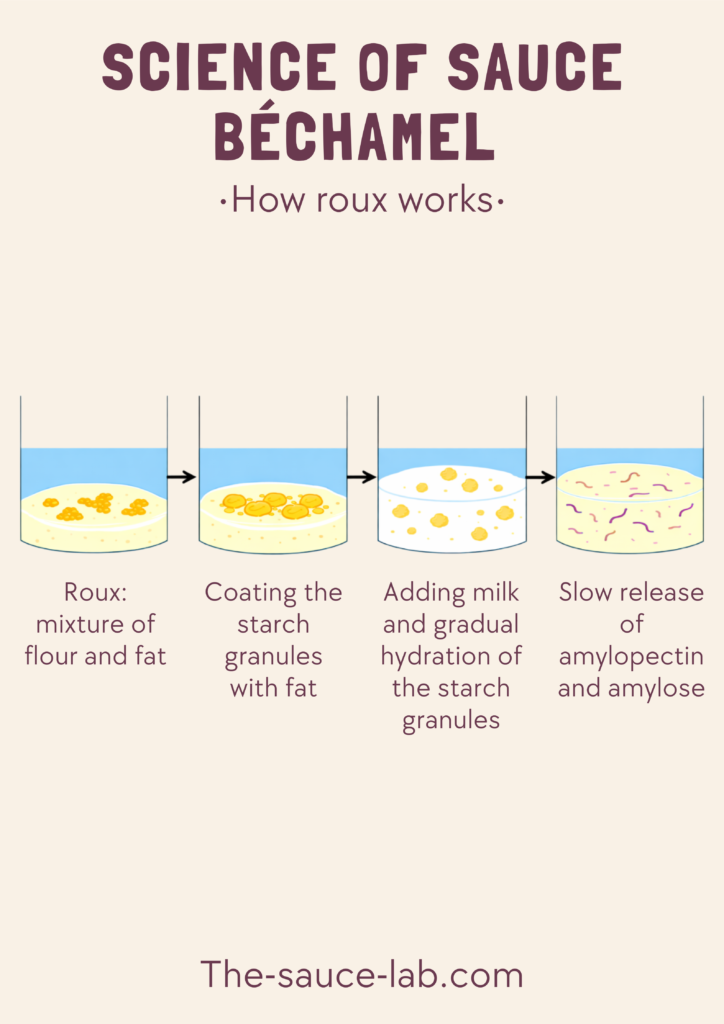

The Science of Roux

Béchamel is a starch-thickened milk emulsion stabilized by fat and heat.

Flour is composed predominantly of carbohydrates in the form of the starch polysaccharides amylose and amylopectin. When water is added to flour too quickly, in the absence of fat, the outermost starch molecules gelatinize immediately, creating a barrier that traps dry flour and forms lumps. This can be prevented by either adding water gradually or stirring vigorously, both of which promote uniform hydration. Unlike a roux, thickening with only liquid occurs quickly, is less smooth, and is more prone to clumping (6,7,8).

A roux is a mixture of equal parts butter and flour. Unlike adding liquid directly to flour, in a roux the starch granules are coated with fat, which delays water penetration and prevents lumping, allowing gradual hydration when liquid is added. This slower penetration occurs because fat and water do not mix readily. Compared to flour thickened directly with water, a roux produces smoother and more stable sauces. Upon heating and hydration, the starch granules swell, and amylose and amylopectin leach into the liquid, forming a three-dimensional mesh that traps water and increases the viscosity of the sauce (6,7,8).

Final Thought

Béchamel is a relatively easy and straightforward sauce to make, but it proves that tasty things in the culinary world do not come from complexity, but from understanding structure, heat control, and process. From royal French kitchens to everyday food classics, sauce Béchamel remains one of the most powerful sauces in the culinary world.

Sauce Béchamel:

Ingredients

Method

- Prepare your ingridinets.

- In a saucepan, over a low-to-medium heat, bring the milk to a simmer. Whisk the milk from time to time to prevent a skin from forming.

- Melt the butter in a saucepan over low-to-medium heat. Add all the flour and stir continuously for 1 to 3 minutes. Be sure not to brown the roux. After around 3 minutes, remove the pan from the heat and let it cool slightly.

- Gradually add the warm milk while whisking constantly to prevent lumps. After adding 3–4ladles of milk and incorporating them into the sauce, you can add the remaining milk at once.Cook the sauce gently for around 30-40 minutes , skimming off the skin that will form.

- Cook the sauce gently for around 30-40 minutes , skimming off the skin that will form.

- Season to taste with salt, white pepper, and freshly grated nutmeg.

- Enjoy you sauce Béchamel .

References:

- Escoffier, A. (1903). Le Guide Culinaire: Aide-mémoire de cuisine pratique. Éditions Flammarion, Paris. First published 1903. ISBN 2-08-200803-7 (2001 printing)

- Delamare, N. (1719–1738). Traité de la police. Paris.

- La Varenne, F. P. de. (1651). Le Cuisinier François. (First mention of white roux sauce).

- Peterson, J. (2008). Sauces: Classical and Contemporary Sauce Making (3rd ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN: 9780470194966

- Larousse, D. P. (1993). The Sauce Bible: Guide to the Saucier’s Craft. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN: 9780471572282.

- Dahiya, S., Bajaj, B. K., Kumar, A., Tiwari, S. K., & Singh, B. (2022). Food thickening agents: Sources, chemistry, properties and applications — A review. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 27, Article e100468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgfs.2022.100468

- Yadav, G. P., Dalbhagat, C. G., & Mishra, H. N. (2022). Effects of extrusion process parameters on cooking characteristics and physicochemical, textural, thermal, pasting, microstructure, and nutritional properties of millet‑based extruded products: A review. Journal of Food Process Engineering, 45(9), e14106. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpe.14106

- han, Y., Dai, H., Ma, L., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Gelatinization, rheological and retrogradation behaviors of waxy rice starch affected by gelatin emulsion and regulation mechanism. Food Hydrocolloids, 159, 110649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.110649