Asafoetida: The Spice That Smells Terrible… Until You Cook It

Introduction

Asafoetida is a dried root sap (latex or oleogum resin) collected from the taproots of some perennial plants of the genus Ferula. These plants belong to the Apiaceae family, native to some parts of the Mediterranean region and parts of Asia like Afghanistan and Iran. The plant is a close relative, in the same botanical group as carrots and fennel (6).

The most important among them is Ferula assafoetida, found in the regions of Iran and Afghanistan. The name “asafoetida” comes from the Persian word for resin—asa—and the Latin word foetida, meaning foul-smelling—a very accurate description of the sulphurous aroma. Other common names for the spice are Hing or Hungu in India, Kama in Afghanistan, Devil’s dung, Stinking gum, A-wei, and Aza in other parts of the world (6).

A Substitute for the Lost Spice Silphium

A spice with high demand in ancient times, called silphium, was widely used in Rome and Greece. It was a highly prized spice for both medicinal and culinary uses. Its origins are most likely the regions of Cyrene, located in modern-day Libya.

Due to the high demand and use, silphium became extinct by the end of the first century AD. As Alexander the Great invaded Asia, asafoetida from Afghanistan and Iran became the new favourite and replacement for silphium. Later, it became popular in Roman cooking. To this day, it is an essential ingredient in Indian cuisine and traditional medicine.

In India, some dietary traditions try to avoid garlic and onions because they are categorized as rajasic or tamasic—meaning they are believed to either stimulate passion, restlessness, and emotional intensity (rajas) or promote heaviness, dullness, and spiritual inertia (tamas). If you smell asafoetida, you will appreciate the strong aroma that resembles the combined aroma of onions and garlic. Therefore, asafoetida is commonly used as a spice substitute because it provides similar flavor, plus an additional digestive benefit, without the same spiritual concerns (7).

Where Asafoetida Comes From

It comes from a plant in the carrot family, native to Central Asia—Turkey, Iran, and Afghanistan. The major producers of asafoetida are Afghanistan and Iran, while the largest importer is India (6).

Plant anatomy

The primary plants that are used for the production of asafoetida are Ferula asafoetida and Ferula foetida. In appearance, they are somewhat similar to a giant carrot, with height reaching 1.5 m (5 feet) and giant roots, also called taproots, similar in shape and form to a carrot. The spice comes from the taproot, which becomes large enough for extraction after about 4–5 years of growth. If you cut open the taproot, the internal part will be thick and fleshy, with milk-like juice and an alliaceous smell (6).

Harvesting of Asafoetida

To obtain the spice, a specific procedure is followed. When the foliage of the plant becomes yellow, the top part of the root is exposed above the ground and scraped. Some days after the scraping is done, an incision is made, forming a wound. After this damage, the plant produces a protective sap that hardens. This is the part that is collected. An important step is to protect the produced sap by shading the root with twigs and stones. The cutting and collecting sequence is repeated until the flow of sap stops.

The yield depends on the plant, with some plants producing 40 g of sap, while certain species can produce as much as 900 g of sap. The harvested sap is stored in pit holes in the ground, where it matures. After some maturation time, the resin is shaped into tears, mass, or paste, with tears being the purest of those three variants. Another possibility is aging the resin in sheep or goat skins (6).

Asafoetida is one of the strangest spices I have encountered so far. Asafoetida’s smell can remind you of onions, garlic, eggs, meat, and white truffles (7).

Varieties of Asafoetida

Asafoetida is classified into two distinct grades, which are Hing and Hingra. Hing is derived chiefly from F. assafoetida, and Hingra is produced from F. foetida. Hing is more desirable and prized because of its richer aroma compared to Hingra. Alongside the difference in aroma, there is also a difference in solubility—Hing is readily dissolvable in water, while Hingra is oil-soluble. There is also a color difference between them—Hing is lighter in color compared to Hingra (6).

Depending on the origin, Hing can be categorized as Irani Hing, which is produced in Iran, and Pathani Hing, which is produced in Afghanistan. Irani Hing will have some impurities compared to the one produced in Afghanistan. Additionally, Irani Hing can be divided into sweet and bitter varieties (6).

Related Gum Resins

There are several similar exudates that are sometimes sold as asafoetida or as substitutes for it. They are not used in cooking, but we will briefly mention them. The most important are:

• Galbanum – a gum resin derived from the plants F. galbaniflua Boiss and Bulise, found in the regions of Northwestern Asia. These too can be found in translucent or yellow-brownish color, with shapes ranging from tears to mass form. It has a somewhat bitter taste and a musky, earthy scent. It contains umbelliferone and is related to coumarin. Galbanum is mostly used in the perfumery industry or for medicinal purposes.

• Sagapenum – derived from F. persica Wild or F. snowilziana D.C. It is darker than galbanum, yellowish to red in color, and semi-transparent. The scent of the exudate is similar to asafoetida, and it has alliaceous notes. It contains sagaresinotannol and umbelliferone. Its primary use is for medicinal purposes.

• Sumbul – also called ammoniac, is extracted from the Ferula sumbul plant. It contains vanillic acid, umbelliferone, and betaine, but it does not show the presence of sulphur. Its primary use is as a fixative in the perfume industry or for some medicinal purposes.

Chemical Composition of Asafoetida

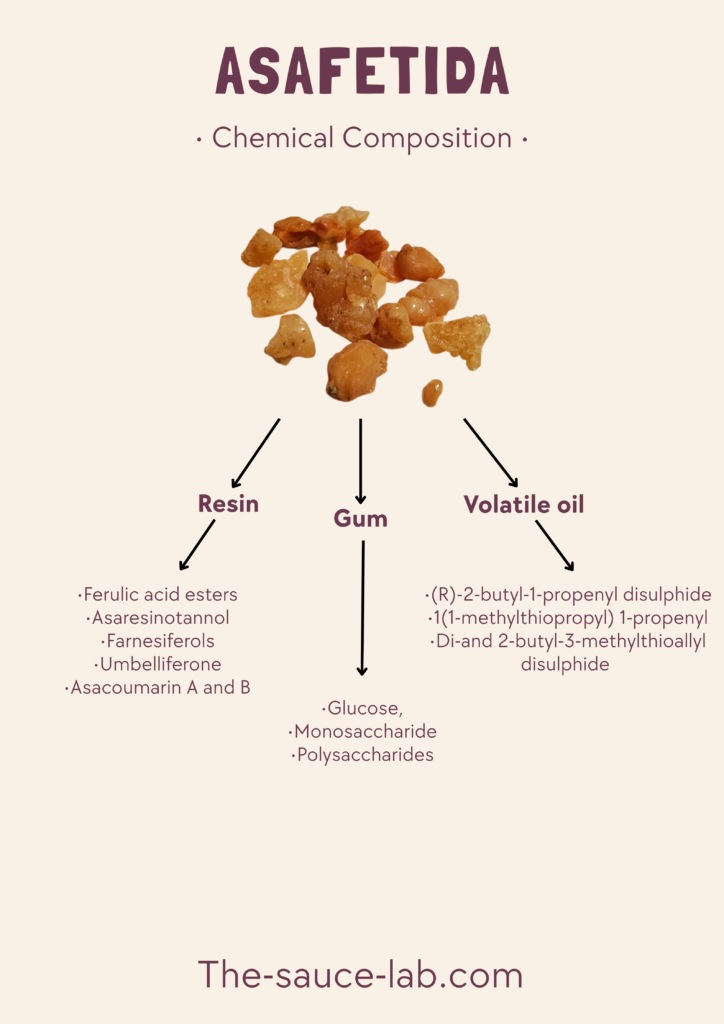

Asafoetida consists mainly of three components (7):

• Resin: 40–64%

• Gum: about 25%

• Volatile oil: 10–17%

Its strong and characteristic smell comes from the presence of several sulphur-containing compounds—di-, tri-, and tetra-sulphides (7). The ones that give it its unique smell are:

• (R)-2-butyl-1-propenyl disulphide

• 1-(1-methylthiopropyl)-1-propenyl

• Di- and 2-butyl-3-methylthioallyl disulphide

The resin also contains ferulic acid esters, coumarin derivatives and complexes (umbelliferone, asacoumarin A, and asacoumarin B), and other compounds, while the gum portion is made of glucose, monosaccharides, and some polysaccharides. There are some differences in the chemical composition of Afghan and Iranian varieties of asafoetida. It is important to note that ferulic acid is converted to coumarin, which has important medical significance (7).

Quality and Adulteration Issues

To increase the “yield,” powdered asafoetida is often mixed with different foreign materials. Common adulterants include:

• Clay or sand

• Gypsum

• Cheaper resins

• Chalk

• Oleogums like galbanum, ammoniacum, and colophony

Because of this, quality standards have been established, especially in India, which is the largest consumer. Under the Government of India’s Prevention of Food Adulteration Act of 1954, Hing must contain less than 15% total ash, 2.5% acid-insoluble ash, and no more than 1% starch, while Hingra may contain no more than 20% total ash, up to 8% acid-insoluble ash, and no more than 1% starch (6).

Main Culinary Asafoetida Products

Even though asafoetida can be sold for its volatile oils (produced by steam distillation), tinctures, or other forms, the most common forms used in the culinary world are the compound form and the resin form. The compounded form of asafoetida is powdered and ready to use, containing approximately 30% asafoetida by total weight. The rest is some form of flour, either rice or wheat. This is mostly because the resin aroma is very strong in its purest form. Asafoetida resin is also sold as chunks that need to be crushed or dissolved before use.

Culinary Uses

Asafoetida is mainly used as a flavouring agent. It should first be bloomed. Take a pinch of it and cook it briefly in hot fat (ghee or oil). This takes the sharpness away and softens the aroma instantly. Asafoetida is a great way to add savouriness to any dish. Because it is mostly used in Indian cuisine, here are some examples of dishes that use asafoetida.

• Classic Dal Tadka (Lentil dish): Start by blooming a pinch (about ¼ teaspoon) of asafoetida in hot ghee. Cook it together with the other aromatics—mustard seeds, cumin seeds, dried red chilies, turmeric, garam masala, onion, and garlic—together with some crushed tomatoes before adding the cooked yellow lentils. It is best served with a side of garlic naan.

• Aloo Gobi (Potato & Cauliflower): Aloo Gobi is one of those timeless Indian dishes that proves comfort food doesn’t need to be complicated. At its heart, it is roasted potatoes and cauliflower combined with fragrant masala made from aromatic spices such as asafoetida, cumin, garlic, ginger, turmeric, coriander, chilies, fenugreek, garam masala, and tomatoes.

• Sambar/Sambhar (South Indian Lentil & Mixed Vegetable Stew): A very interesting stew made with dal (lentils), tamarind broth, asafoetida, and other spices, together with mixed vegetables. Other aromatics also include coriander seeds, dry red chilies (typically Kashmiri or Byadgi varieties), fenugreek seeds (methi), cumin seeds, turmeric, curry leaves, and mustard seeds.

• Kala Chana Masala (Black Chickpea Curry): A black chickpea (kala chana) curry flavoured with asafoetida, cumin seeds, onions, garlic, green chilies, ginger, Kashmiri chili powder, turmeric, coriander, garam masala, and tomatoes.

• Kaddu ki Subzi (Pumpkin/Squash Stir-fry): A dish made with pumpkin, spices, and herbs. Asafoetida complements the sweetness of pumpkin, particularly in Maharashtrian-style recipes.

• Mango (Hing ka Achar, Mango Hing Pickle) or Lemon Pickle: Asafoetida here acts as a preservative and flavouring agent in traditional, pungent Indian pickles.

• Masala Poha: Poha is an Indian dish made from flattened rice cooked with onions, peanuts, potatoes, spices including asafoetida, and often topped with coriander. It comes in several varieties, like Kanda Poha and Indori Poha.

• Upma: Upma is a breakfast dish from South India, made from roasted rava (semolina) cooked with onions, asafoetida, mustard seeds, curry leaves, vegetables, and spices, resulting in a soft, comforting, and nourishing meal. It has many regional variations, is quick to prepare, and is traditionally enjoyed for breakfast or as a light snack.

• Lahndi or Landai (preserved meat): A traditional Pashtun (Afghan) dish made with salt and asafoetida as curing agents for air-dried meat. It is prepared mainly from lamb or mutton (halal-slaughtered), which is cleaned, rubbed with salt and asafoetida, and then left to cure until winter.

Traditional Medicinal Uses

Asafoetida has long been used in traditional medicine. It has been applied for (1-5):

• Asthma

• Digestive disorders

• Intestinal parasites

• Pain relief

• Neurological conditions Most of the biological activities of asafoetida include:

• Antioxidant activity – reduces oxidative stress and free-radical damage (1,2).

• Neuroprotective and memory-enhancing effects – improves learning, memory, and neuronal survival in experimental models (1,3).

• Antimicrobial activity – antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral effects reported (2).

• Anticancer/anticarcinogenic activity – inhibitory effects on cancer cell growth (1).

• Anti-inflammatory activity – reduces inflammation and oxidative tissue damage (1,4).

• Antispasmodic and carminative effects – relaxes smooth muscle and aids digestion (3).

• Hypotensive and cardiovascular effects – reported blood-pressure-lowering and blood-thinning properties (3).

• Hepatoprotective activity – protective effects against liver injury (1,4).

• Anthelmintic (anti-parasitic) activity – traditional and experimental anti-worm effects (4).

• Anxiolytic and sedative effects – calming and nervous-system-modulating properties (3).

Safety Considerations

Large amounts of raw asafoetida may cause:

• Headache

• Nausea

• Vomiting

• Throat irritation

• Stomach pain

It should be avoided:

• During pregnancy (it is a natural contraceptive and potential abortifacient)

• During breastfeeding—coumarin in asafoetida could pass into breast milk and cause blood disorders in the nursing infant

• In infants, where it may be dangerous because it might cause certain blood disorders

Storage: Keep the Aroma Contained

Asafoetida is one of the most aromatic ingredients in the spice world, and that aroma spreads easily. If it isn’t stored properly, it can quickly perfume your entire spice cabinet—or even your pantry—with its pungent scent.

To keep both the asafoetida and your other spices in good condition, always store it in an airtight container. A small glass jar with a tight-fitting lid works best. Many cooks even keep that jar inside a second sealed container or plastic bag to prevent the smell from escaping.

Place it in a cool, dry, and dark location, just like other spices. Avoid storing it near heat sources such as the stove, and keep it away from moisture, which can cause clumping.

Because of its powerful aroma, it’s best to store asafoetida separately from delicate spices like cinnamon, cardamom, or saffron. Otherwise, they may absorb its smell over time.

Properly stored, asafoetida will keep its potency for a long time—and your spice rack will stay pleasantly fragrant instead of overwhelmingly pungent.

A Wild Spice with Untapped Potential

Asafoetida remains one of the world’s most unusual spices—a resin harvested from Ferula plants grown natively in Iran and Afghanistan. The “milk-like juice” with alliaceous aroma is collected from the taproot and aged into a seasoning. Despite its sharp aroma when raw, it transforms into a mellow, savory enhancer when bloomed in hot fat, adding depth to dishes from dal to pickles. It also offers traditional medicinal benefits such as digestive support and antimicrobial activity. Long used as a substitute for extinct silphium, asafoetida still feels like a rediscovered treasure—bold, ancient, and full of culinary potential waiting to be explored.

References:

- Mahendra, P., & Bisht, S. (2012). Ferula asafoetida: Traditional uses and pharmacological activity. Pharmacognosy Reviews, 6(12), 141–146.

- Iranshahy, M., & Iranshahi, M. (2011). Traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of asafoetida (Ferula assa-foetida oleo-gum-resin): A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 134(1), 1–10.

- Amalraj, A., & Gopi, S. (2017). Biological activities and medicinal properties of asafoetida: A review. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, 7(3), 347–359.

- Upadhyay, P. K. (2017). Pharmacological activities and therapeutic uses of resins obtained from Ferula asafoetida Linn.: A review. International Journal of Green Pharmacy.

- Thulluri, et al. (2025). Protective effects of Ferula asafoetida against formaldehyde-induced damage.

- Peter, K. V. (Ed.). (2012). Handbook of herbs and spices (2nd ed., Vol. 2). Woodhead Publishing.

- McGee, H. (2004). On food and cooking: The science and lore of the kitchen. Scribner.