Rice: Varieties, Structure, and Classification

What Rice Is

Rice is a cereal, cultivated for its edible seeds. It is a staple food for over half of the world’s population, mainly in Asia and Africa.

Rice is cultivated in more than 100 countries and six continents; the one exception is Antarctica. The genus Oryza includes 22 species, from which two are domesticated. Oryza sativa (Asian rice) accounts for most of the global rice production and consumption (1), while Oryza glaberrima (African rice) is less widely grown, mainly in West Africa. Around 20% of the rice grown in Africa is O. glaberrima. It has been largely replaced by Asian rice (2).

Rice is a plant grown in a variety of water regimes and soils. According to the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), there are five main rice cultivation ecosystems:

- Irrigated rice – 47.4% of global output

- Rainfed lowland rice – 27.6%

- Upland rice – 16.6%

- Deep water rice and tidal wetland rice – 8.4% combined

Rice is an ideal for cultivation, especially in the tropical and subtropical regions, due to biological, environmental, and some socio-economic factors. It provides calorie-rich food for billions of people worldwide (3,13).

History of rice

Human hunter-gatherers began harvesting wild rice in China and South Asia more than 10,000 years ago.

Over time, humans unconsciously selected plants with desirable traits such as larger grains or non-shattering seeds—a process known as domestication. Asian rice (Oryza sativa japonica) was domesticated from the wild rice Oryza rufipogon roughly 8,000–10,000 years ago (around 7000–5000 BCE) in the Yangtze and Pearl Rivers regions in southern China. O. sativa indica spread to the west and south, interbreeding with local wild rice, reaching the Indian subcontinent, Korea, and Japan. Independently, Oryza glaberrima, was domesticated from Oryza barthii in the West Africa some 3000–4000 years ago. From Asia, rice spread to Persia and Mesopotamia, Europe, (particularly Al-Andalus and later Sicily. Spanish and Portuguese introduced rice to America, where African agricultural knowledge influenced cultivation (4, 5).

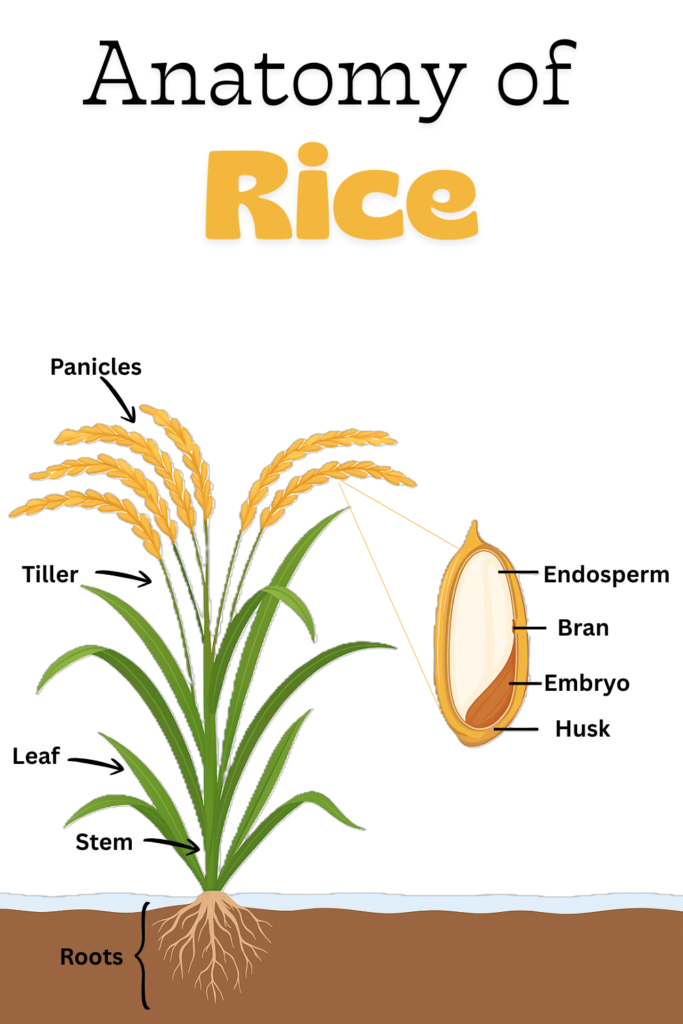

Rice Plant and Grain Anatomy

Rice plants have a fibrous root system, anchoring the plant and absorbing water and nutrients. Hollow, stiff stems (culms) support leaves and tillers, which produce panicles—branched flower clusters that develop into grains after fertilization.

Each grain of rice is a seed containing enough energy and nutrients to start of new generation. The grain of rice serves as a storage organ. The plant converts the excess glucose into starch and stores it in the endosperm which along with the protective bran layer (husk), and an embryo (rice germ), forms the rice grain (caryopsis).

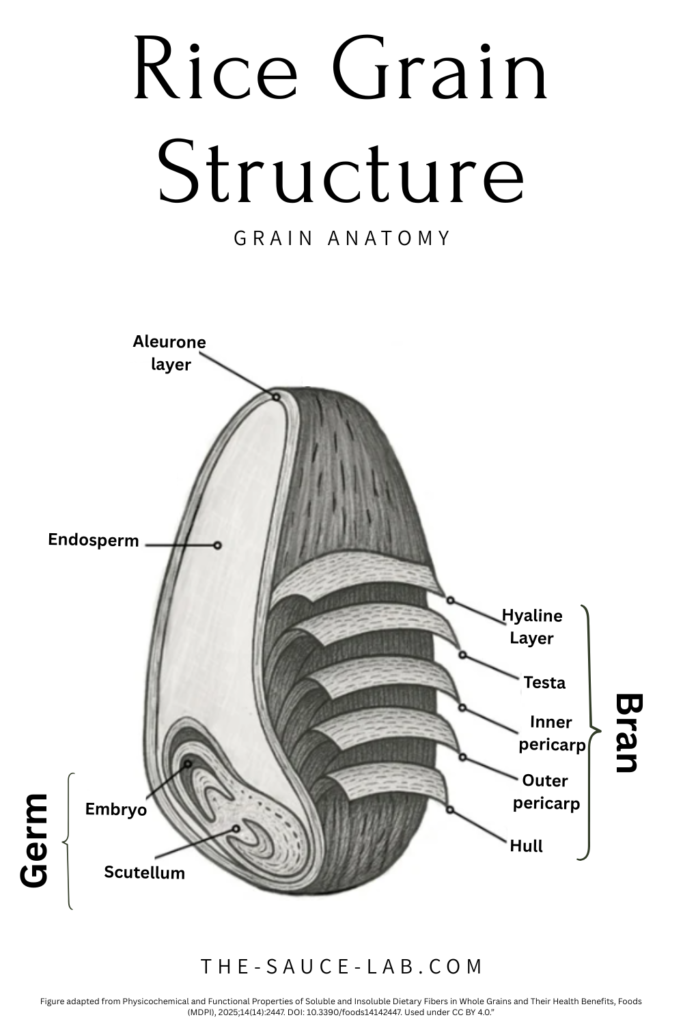

Rice grains are specialized structures consisting of the following structures:

- Hull – protective outer layer, removed to produce brown rice

- Bran – three layers: pericarp, seed coat, and nucellar tissue

- Embryo (germ) – provides vitamins and essential fatty acids

- Endosperm – stores starch and protein

The hull accounts for approximately 20% of rough rice. The rest of the brown rice, ~90–91% is endosperm, with the rest comprising outer bran layer (pericarp, aleurone, seed coat), germ, and scutellum.

Endosperm cell contains organelles called amyloplasts which are synthesizing and store starch. The starch granules (3 to 9 µm in size) are surrounded by spherical protein bodies (0.5 to 4 µm in size).

Generally, starch is concentrated near the center while the protein is near the surface– explaining why when rice is refined, it loses nutrients.

Approximate composition varies by grain component:

- Endosperm: 85–90% carbohydrates, 7–10% protein, 0.5–1.5% lipids

- Aleurone, seed coat, nucellus: 35–45% carbs, 15–25% protein, 15–25% lipids

- Pericarp: 60–70% carbs (cellulose, hemicellulose), remainder lipids and proteins

- Germ: 35% carbs, 20% protein, 35% lipids (6).

Starch Chemistry

The endosperm, which makes up ~90% of the grain, is rich in starch—the main component humans consume. Starch affects both texture and taste.

Rice starch is composed of amylose and amylopectin.

- Amylose is smaller, and it’s made up of around 1,000 glucose molecules arranged in a straight chain.

- Amylopectin is made up of 5,000 to 20,000 glucose molecules, has many branches, making the molecule bulkier.

The relative proportion of each kind can vary depending on the variety of rice. This fact will lay the foundation for the preparation of the different types of rice (7,8,12).

If the rice is high in amylose, the grains will stay separate after cooking, while types with high amylopectin will become sticky after cooking (7,8,12).

GELATION

When a rice seed is cooked, the water will be absorbed by the starch granules. They will swell, causing them to separate from each other. This is gelation, and it occurs at 59–79ºC (138–174ºF) depending on the rice variety. Since amylose is linear, its molecules are tightly packed together making it harder for the water to keep them apart. This will requiring higher temperatures, more water, or cooking time. Since amylopectin is with branched molecule, it will require lower temperature, amount of water, and cooking time (7,8).

RETROGRADATION

Upon cooling below the gelation point, 60–70ºC (140–160ºF), starch and water will reassemble. The amylose molecules will reform very quickly, while for amylopectin molecules will take longer. This explains why different rice types behave differently.

Rice high in amylose will be firm and springy right after cooking but will become very firm and hard after refrigeration. Rice low in amylose is going to be softer and sticky after cooking, and it will be softer after refrigeration (7.8).

We can summarize those facts as follows:

• Amylose will form stronger and firmer gels, contributing to its hardness, is less water-soluble, and needs more heat to gelatinize. It will have firmer, separate grains after cooking.

• Amylopectin is more water-soluble and will be stickier and softer.

Grain Length Classification

Genetic classification of rice

Rice has two subspecies: Indica and Japonica.

• Indica rice is grown in the tropics and subtropics, it is long and firm and is with high amylose content.

• Japonica rice is grown in the tropics (known there as javanica) and in temperate climates, has shorter and stickier grains, and is low in amylose.

Grain morphology and starch composition

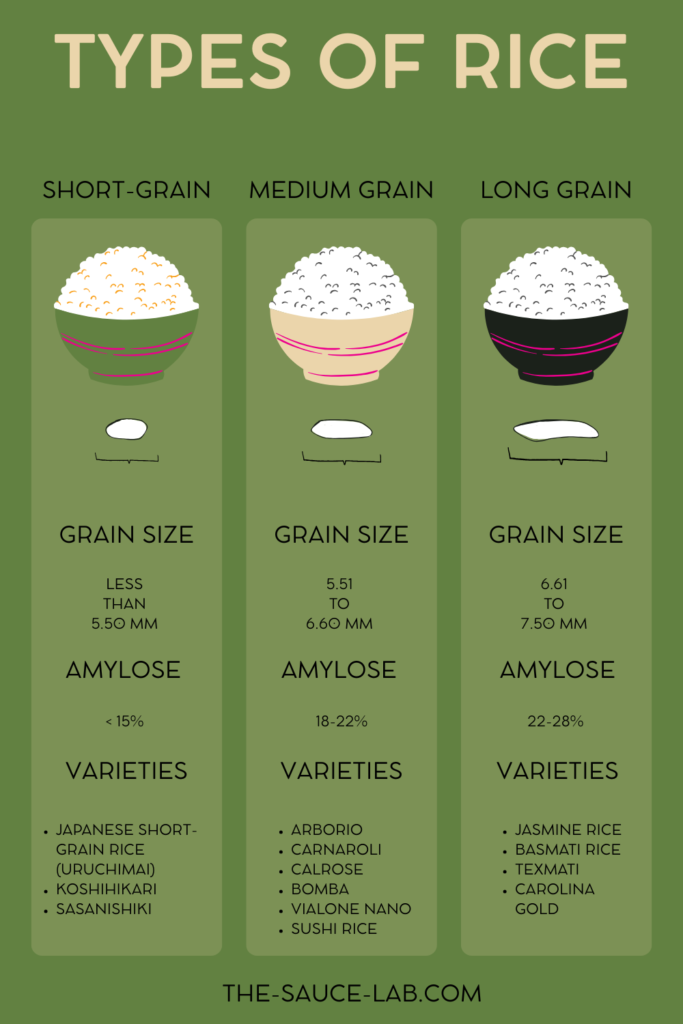

Rice can also be categorized according to the lengths of the actual grain:

- Long-grain rice is above 6.61 mm long. It is high in amylose (22–28%), it will produce firm and separate grains. It is grown in China and India. Examples include Jasmine Rice, Basmati Rice, Texmati, and Carolina Gold (13).

- Medium-grain rice length is 5.51 to 6.60 mm. It contains around 18–22% amylose— It cooks up tender and moist and slightly sticky, making it ideal for dishes like risotto, paella, and sushi. Examples include Arborio, Carnaroli, Calrose, Bomba, and Vialone Nano (13).

- Short-grain rice is usually less than 5.50 mm long. It contains less than 15% amylose, which makes it sticky, soft, and plump when cooked. It is mainly used in China, Japan, and Korea. It is ideal for making sushi. Some examples include Japanese short-grain rice (uruchimai), Sushi rice (often the same as Japanese short-grain), Koshihikari, and Sasanishiki (13).

Special groups of rice

- Aromatic rice: In its length is a class of long-to-medium-grain rice. It is high in volatile compounds. Some examples include Basmati, Jasmine, and Della rices; Dulha Bhog from Bangladesh; Khao Dawk Mali grown in Thailand; Azucena and Milfor of the Philippines; and Rojolele of Indonesia.

- Glutinous: In its length is a class of short-grain rice with most of the endosperm being amylopectin. When cooked, it becomes sticky and has the tendency to disintegrate. It is often used for sweets rather than salty dishes. It is the standard rice in northern Thailand and Laos.

Processing and Different Forms of Rice

Most of the consumed rice is milled and polished removing the bran, the germ, and the aleurone layer. Even though those layers contain fibers, oils, B vitamins, and proteins, they are removed because rice in this form is easier to cook and chew, has better appearance, and cab be kept for months.

Polished rice

It is milled to remove all the layers, leaving only the endosperm. Any variety of rice can be sold in this form. It cooks faster and has a softer, less chewy texture, but the removal of all those layers decreases the aroma and flavour.

Brown rice

Brown rice retains its germ, bran, and aleurone layers. Any variety of rice can be sold in this form. Compared with polished rice, it takes longer to cook, it is chewier, but it has a rich, nutty aroma. Moreover it has shorter shelf-life because of the oils readily present in the germ, bran, and aleurone layers. It is best stored in the refrigerator.

Parboiled rice

It is mainly used in India and Pakistan. While still fresh, it is soaked, boiled or steamed, and dried. This causes the vitamins located in the bran and germ to diffuse into the endosperm, making the rice more nutritious. This improves the texture by hardening the starch and decreasing the stickiness. Soaking activates enzymes that generate sugars and amino acids, participating in the Maillard reactions during cooking, giving it a nutty flavour. Partial breakdown of lignin also produces vanillin and similar compounds, contributing to the flavour. Parboiled rice takes longer to cook and is quite firm.

Wild rice

Zizania palustris produces very long grains, dark seeds with complex flavour. Native to North America, this rice takes longer to cook due to its intact bran layer and offers a distinct nutty, earthy flavour with a firm, chewy texture (12).

Aromatic Compounds in Rice

Rice varieties have a wide range of flavours and textures. Aromatic rice varieties, such as Jasmine and Basmati, which are very popular worldwide, inevitably increase the demand and higher market prices when compared to non-fragrant rice.

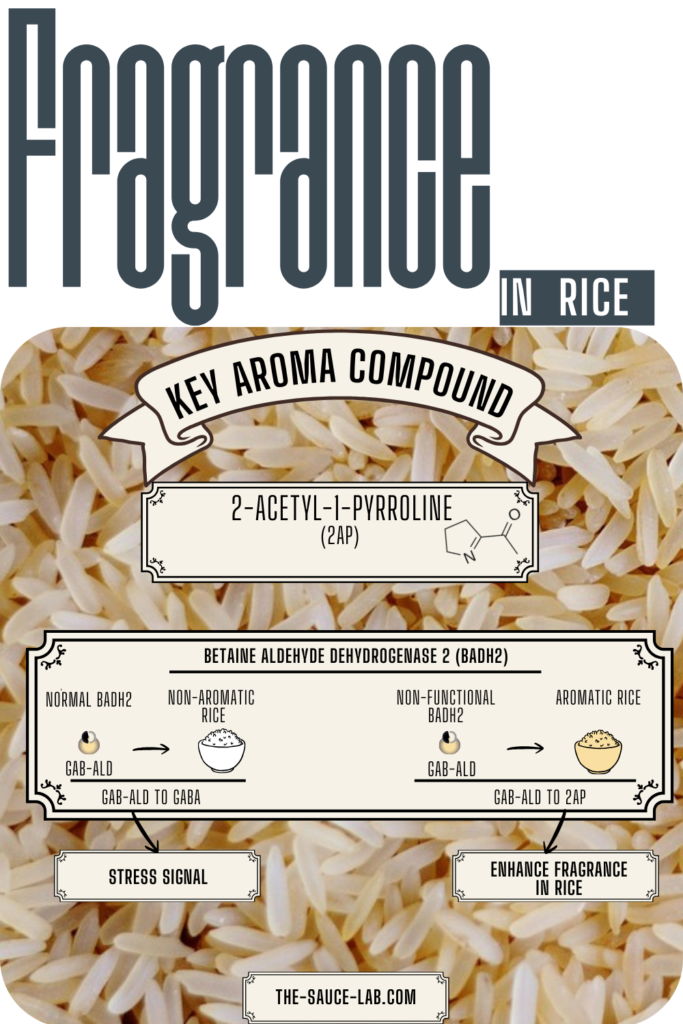

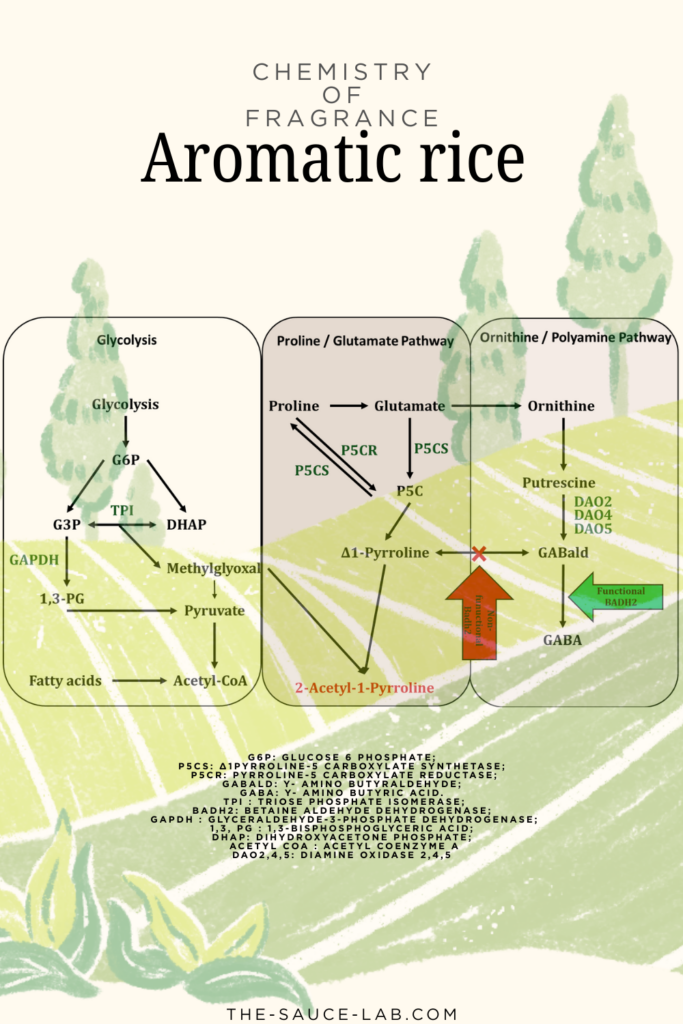

One of the main contributors to the aroma is the molecule 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (2AP), responsible for the characteristic fragrance of those rices.

Betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (BADH2) regulates the presence and accumulation of 2AP in rice. BADH2 is from the aldehyde dehydrogenase family (ALDH) of NAD(P)⁺-dependent enzymes that can catalyse the oxidation of aldehydes to carboxylic acids. In non-aromatic rices, the BADH2 enzyme converts GAB-ald (γ-aminobutyraldehyde) precursor into GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), a signalling stress molecule capable of activating antioxidant defences- no distinct smell. If there is a decrease or loss-of-function of BADH2, this leads to the GAB-ald accumulation, which is subsequently converted into 2AP (9,10,11,12).

Global Rice Map

Here’s a breakdown of rice used by country or region:

Asia:

- India/Pakistan: Basmati (long-grain) and Sona Masuri (medium-grain).

- Thailand: Jasmine rice (long-grain).

- Japan: Koshihikari/Uruchimai (short-grain) and Mochigome (glutinous).

Europe:

- Italy: Arborio, Carnaroli, Baldo (medium-grain).

- Spain: Bomba and Arroz del Delta del Ebro (short-grain).

- France: Riz de Camargue (medium-grain).

- Portugal: Arroz Carolino das Lezírias Ribatejanas (medium-grain).

North America:

- USA (California): Calrose (medium-grain).

- USA (South): Carolina Gold Rice (long-grain).

- North America (General): Wild Rice (long-grain).

Africa:

- Nigeria: Ofada (aromatic, medium-grain) and Abakaliki rice (long-grain).

Australia:

- Australia: Varieties like Doongara (long-grain), Koshihikari (short-grain), etc.

Storage Conditions

- Rice should be stored in a cool, dry place in an airtight container to protect it from moisture, insects, and odors.

- Polished (white) rice can be kept at room temperature for long periods because it contains very little oil.

- Brown and aromatic rice contain more natural oils and should ideally be stored in the refrigerator or freezer to prevent rancidity and preserve flavour.

- Proper storage helps maintain rice quality, taste, and aroma over time.

References

- Muthayya, S., Sugimoto, J. D., Montgomery, S., & Maberly, G. F. (2014). An overview of global rice production, supply, trade, and consumption. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1324(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12540

- Linares, O. F. (2002). African rice (Oryza glaberrima): history and future potential. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99(25), 16360–16365. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.252604599

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations & International Rice Research Institute. Resources and services — International Rice Research Institute. Retrieved December 20, 2025, from https://www.irri.org/resources-and-services

- Zhang, Q., Chen, W., Sun, L., Zhao, F., Huang, B., Yang, W., … & Han, B. (2012). The genome of Oryza sativa ssp. indica and its evolutionary history. Nature, 490(7421), 497–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11532

- Liu, L., Xie, K., Li, J., & Zhang, J. (2022). Advances in rice functional genomics and molecular breeding. Molecular Plant, 15(5), 761–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2022.03.009

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rice in human nutrition — Grain structure and composition. FAO, 2004. Rice in human nutrition – Grain structure, composition and consumers’ criteria for quality

- Farooq, M. A., & Yu, J. (2025). Starches in rice: Effects of rice variety and processing/cooking methods on their glycemic index. Foods, 14(12), 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14122022

- Zhou, Z., Robards, K., Helliwell, S., & Blanchard, C. (2002). Composition and functional properties of rice. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 37(8), 849–868. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2621.2002.00625.x

- Chen, S., Yang, Y., Shi, W., Ji, Q., He, F., Zhang, Z., Cheng, Z., Liu, X., & Xu, M. (2008). Badh2, encoding betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase, inhibits the biosynthesis of 2‑acetyl‑1‑pyrroline, a major component in rice fragrance. The Plant Cell, 20(7), 1850–1861. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.108.058917

- Roy, S., Banerjee, A., Basak, N., Kumar, J., & Mandal, N. P. (2020). Aromatic rice. In The future of rice demand: Quality beyond productivity (pp. 251–282). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978‑3‑030‑37510‑2_11

- Hinge, V. R., Patil, H. B., & Nadaf, A. B. (2016). Aroma volatile analyses and 2AP characterization at various developmental stages in Basmati and non‑Basmati scented rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars. Rice, 9(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284‑016‑0113‑6

- McGee, H. (2004). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen (Completely Revised and Updated). New York: Scribner. ISBN 1‑4165‑5637‑0.

- IRRI (1979). The chemical basis of rice grain quality. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Chemical Aspects of Rice Grain Quality. International Rice Research Institute, Los Baños, Philippines.