Brainsed Oxtail – From Structure to Perfectly Braised Dish

Introduction

Braised oxtail is a dish made by slowly cooking oxtails for a few hour in combination with aromatics and stock. In cooking, the term oxtail refers to the tail of cattle in general, not specifically the tail of an ox. It is a piece rich in collagen, bone marrow, proteins and some minerals. The richness of the dish is accomplished by slow braising that will allow the collagen to become gelatine, resulting in a melt-in-your-mouth feel. The result is a rich, flavourful dish where the meat is so tender it falls directly from the bone.

The key to the perfectly cooked oxtails is braising – low and slow. You first sear the meat in order to develop a nice deep flavour (Maillard reaction) and then gently simmer it for a few hours with vegetables, herbs and stock. The result is silky and very tender rich meat with sauce from which you will want more.

If you are looking for bold flavours and you want to surprise someone, Braised oxtails are the recipe to try.

Unlike Korean (Kkori Jjim, 꼬리찜) or China (红烧牛尾) and Caribbean/Jamaican style oxtail, which rely on heavy seasoning and exotic spices, this oxtail dish relies of accessible seasonal products emphasizing on the balance between tastes: balance between sweetness from the carrots, onions to the savouriness of the meat and herbs.

For This Recipe, You Will Need:

- Oxtail – 2 tails, cut between the joints and trimmed from excess fat

- Onions – 2 mediums-sized, finely chopped.

- Carrots – 2 medium-sized, sliced into cubes.

- Celery stalk – 1 celery stalks, sliced into cubes.

- Garlic – 3–4 cloves, finely chopped.

- Tomato paste – 1 tablespoon.

- White wine – 200 ml (dry wine works best).

- Beef stock – 2 L (2000ml).

- 3 freshly grated Tomatoes (if in season) or one can of canned Tomatoes

- Oil – olive oil, for searing/browning.

- Fresh parsley – whole, with the stems.

- Fresh Thyme- whole, with the stems.

- Bay leaf – 1 leaf.

- Salt – to taste.

- Black pepper – to taste.

Step-by-Step Recipe for Braised Oxtail

- Gather and prepare the ingredients.

- If your oxtail is a whole piece, you need to cut it between the joints. Alternatively, you can ask your butcher to do that for you.

- Pat dry the oxtail with a paper towel and season lightly with salt and pepper.

- Sear the meat. In a heavy pot, heat olive oil over medium-high heat and brown the oxtail pieces on one side.

- Rotate and do the same on the other side as well. This step will ensure the development of deep flavour through the Maillard reaction and will form a caramelized fond on the bottom of the pan.

- Remove and set aside.

- In the same pot, sauté the onions, carrots, and celery. Cook for around 2 minutes until soft and golden. The fond that was created from the meat will be partially removed from the acidity of the onions. Add the garlic, tomato paste, and sprig of thyme. Stir for another minute. Again, a caramelized fond at the bottom of the pan will be created.

- Deglaze with the white wine and cook until the alcohol evaporates – 2 to 3 min.

- Add the grated tomatoes (canned tomatoes will also work).

- Add the beef stock.

- In a cheesecloth add your bay leaf, thyme and parsley and tie it.

- Next, return the meat to the pot, add the bouquet garni and pour in enough beef stock to cover the oxtail. Some of the stock will eventually evaporate and you need to refill it again.

- Cover and simmer at low temperature for 2.5-3 h. (150 –180 min) at a low temperature.

- After 150-180 min the meat should fall from the bone.

- Adjust with salt and pepper, to taste.

- OPTIONAL: for a very nice finish you can remove the already cooked oxtails and set them aside. Strain the cooked liquid through a fine sieve or a cheesecloth into a new pan and reduce until it reaches the consistency of thick sauce. Again, check and adjust your seasoning at this step.

- Serve the oxtails and the sauce. Garnish it with a freshly chopped parsley. The dish pairs well with potato purée, sauce Chimichurri, rice and freshly baked sourdough bread.

The Science Behind Tender Braised Oxtail

Anatomy of the Tail Region

A cattle’s tail is the posterior -most portion of the spine made up of 18-20 caudal vertebrates that are interconnected to each other with intervertebral discs and supported by ligaments (bone to bone connection) and muscles. The tail also contains blood vessels, nerves and ends with a fringe of hair.

The muscles of the tail are an extension of the muscles of the back and pelvis.

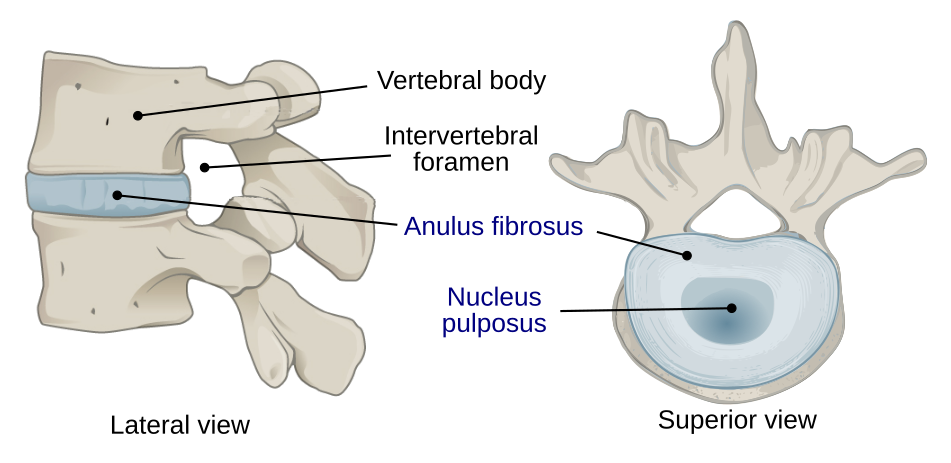

The space between the vertebras is occupied by a substance that helps with the absorption of impact due to bodily activities, keeping the vertebrae separate.

The intervertebral disc consists of a central gel-like structure nucleus pulposus and an outlining ring the anulus fibrosus. Both of those structures contain water and collagen (mainly types I and II).

Photo attribution: Wikimedia commons – Author Jmarchn.

Creating Flavours — Searing Before Braising

By browning the meat first, you create complex flavour molecules (Maillard compounds), which contribute to the deep taste that is characteristic for braised dishes.

Maillard reaction is a non-enzymatic reaction contributing to browning, influencing the odor (smell sensation, perceived by the nose), taste (perceived by the taste receptors in the mouth), but also mouthfeel (texture such as tenderness, juiciness, crunchiness etc) and colour (perceived by the eyes). There are a handful of factors that influence the reaction result or the desired sensory qualities of food, such as temperature, time, water activity, pH, types of amino acids and sugars, and vitamin C. In a nutshell, Maillard reaction is a complex reaction between proteins, amino acids (building blocks of proteins), and sugars. This process generates a variety of end products that contribute to the characteristic colour, flavour, and texture.

Collagen Breakdown = Tender Meat + Silky Sauce

Connective tissue is the structure that provides the connection within the body — between muscles and bones (tendons) and between bones and bones (ligaments). It is also present between the muscle fibres that make up the muscles.

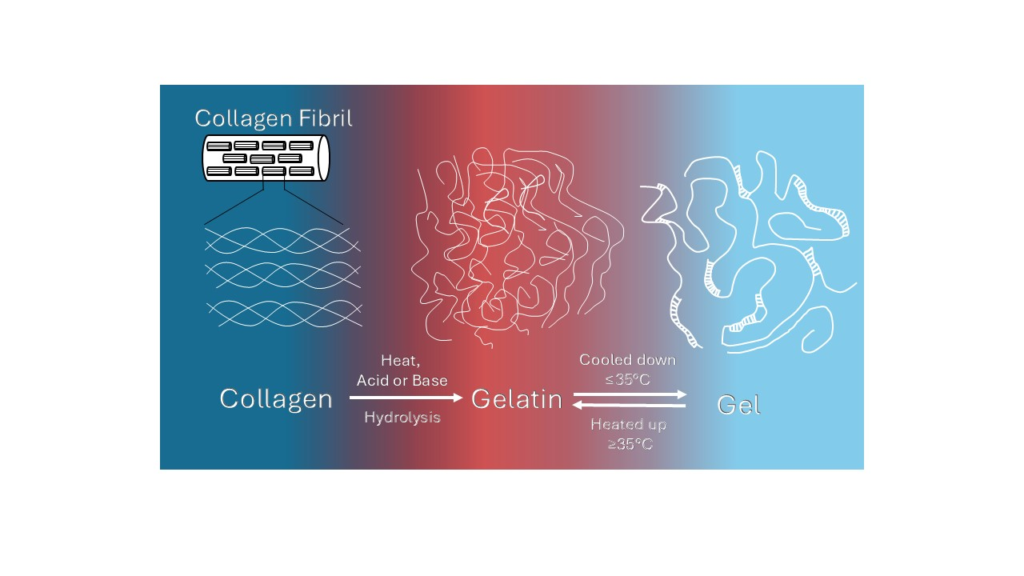

Oxtail is thus rich in connective tissue proteins, particularly collagen. Collagen molecule consists of three strands (peptide chains) that are twisted in a helix. Those strands are held together with bonds (hydrogen and covalent), giving collagen a great strength. Collagen is naturally insoluble in water, but under the right conditions, it converts to gelatine (gelation)— a form that is completely soluble in water in the temperature range above 35–40 °C.

The best way to cook collagenous rich meat tissue is on a low temperature for prolonged periods of time. During the slow cooking process, collagen gradually undergoes denaturation and hydrolysis. The bonds that are keeping the three strands together are broken, resulting in the separation of the separate strands of the collagen. Alongside the denaturation, the heat also helps proteins to be “cut” into small parts called peptides through hydrolysis. The result is shorter single strands that are soluble in water compared to the large molecules of the collagen (insoluble).

As the dish cools, the gelatine strands will try to reassemble themselves into collagen. They will not be able to, but some parts of the strands will be able to connect to each other forming a three-dimensional network. This gives gelatine the capacity to swell, absorbing at least 5 times its weights in water, making the solution more viscous. This thickens the sauce and gives the dish a nice mouthfeel.

Additionally braising at low, steady heat softens the meat, converts the available collagen between the muscle’s fibres into gelatine creating a tender, juice bite.

Take away message

The anatomical structure of the tail, and the behaviour of collagen itself when heated, provides the real reason behind why braising would work perfectly. Knowing how to develop good Maillard reactions and gradual collagen hydrolysis, the dish develops layered flavour with a characteristic silkiness. This is where the interaction between chemistry and culinary technique works in making braised oxtail so different. When cooked low and slow, biological structure turns into gastronomic pleasure.

Braised oxtail

Ingredients

Method

- Gather and prepare the ingredients.

- If your oxtail is a whole piece, you need to cut it between the joints.

- Pat dry the oxtail and season with salt and pepper.

- Heat olive oil over medium-high heat .

- Sear the meat on one side, then rotate and do the same on the other side.

- Remove and set aside.

- In the same pot, sauté the onions, carrots, and celery. Cook for around 2 minutes until soft and golden.

- Add the garlic, tomato paste, and sprig of thyme and stir for a 1-2 min.

- Deglaze with the white wine and cook until the alcohol evaporates – 2 to 3 min.

- Add the grated tomatoes (or canned ones).

- Add the beef stock.

- In a cheesecloth add your bay leaf, thyme and parsley and tie it.

- Return the meat to the pot, add the bouquet garni and pour in enough beef stock to cover the oxtail.

- Cover and simmer at low temperature for 2.5-3 h. (150 –180 min) at a low temperature.

- OPTIONAL: For a smooth and silky sauce- remove the already cooked oxtails and set them aside. Strain the cooked liquid through a fine sieve or a cheesecloth into a new pan and reduce until it reaches the consistency of thick sauce.

- Check and adjust your seasoning with salt and pepper.

- Serve the oxtails and the sauce. Garnish it with a freshly chopped parsley. The dish pairs well with potato purée, sauce Chimichurri, rice and freshly baked sourdough bread.

References:

- Budras, K.-D., Habel, R. E., Wünsche, A., & Buda, S. “Bovine Anatomy: An Illustrated Text.” Schlütersche GmbH & Co. KG, ISBN 3-89993-000-2.

- Cramer, G. D., & Darby, S. A. (Eds.). Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and ANS. Mosby, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2009-0-42801-0 (ISBN 978-0-323-07954-9).

- El Hosry, L., Elias, V., Chamoun, V., Halawi, M., Cayot, P., Nehme, A., & Bou-Maroun, E. “Maillard Reaction: Mechanism, Influencing Parameters, Advantages, Disadvantages, and Food Industrial Applications: A Review.” Foods. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111881

- Kramer, D. L. “Gels for Photographic Emulsions.” Gelatine Handbook. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043152-6/00622-7